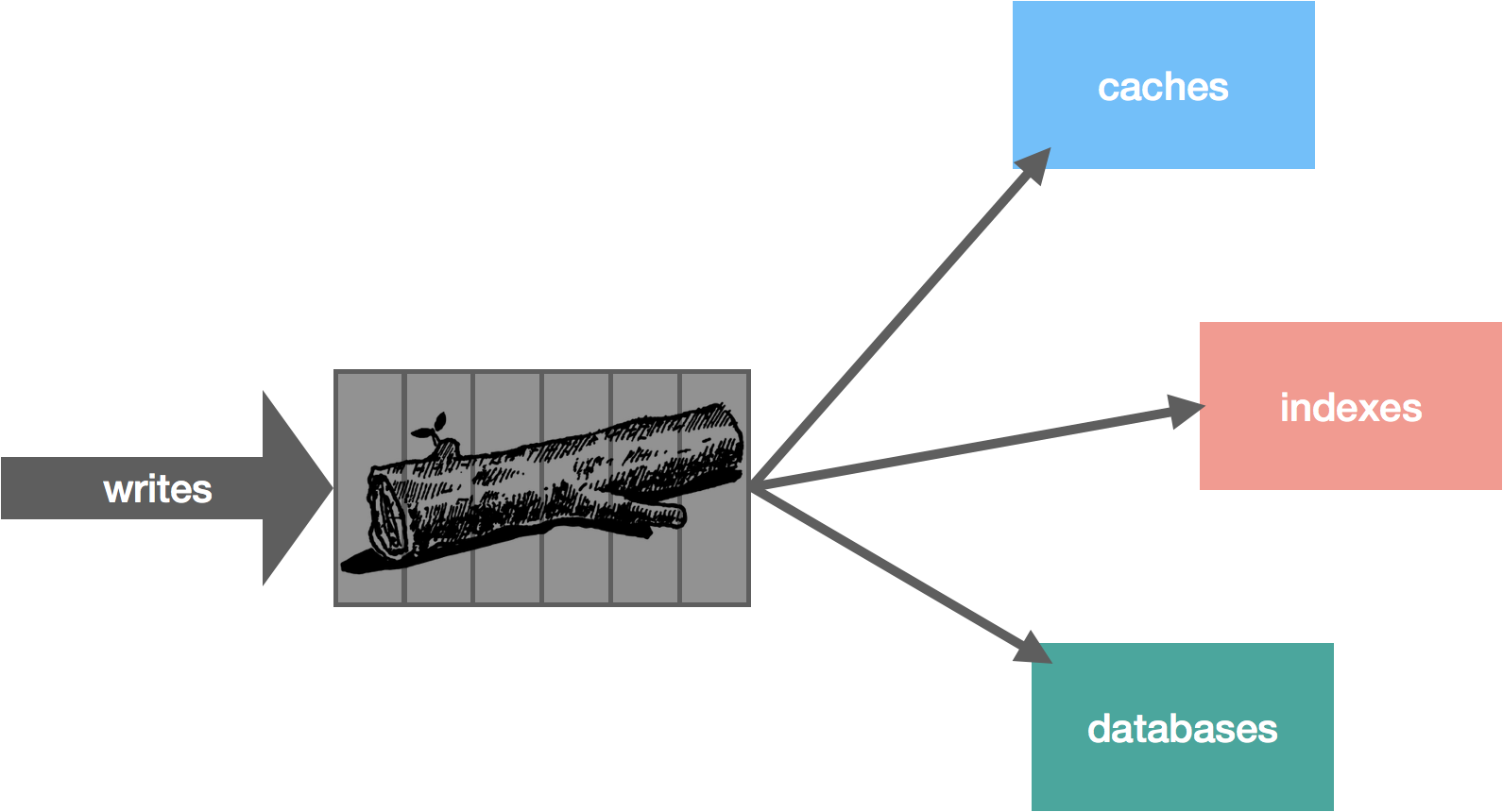

In part one of this series we introduced the idea of a message log, touched on why it’s useful, and discussed the storage mechanics behind it. In part two, we discuss data replication.

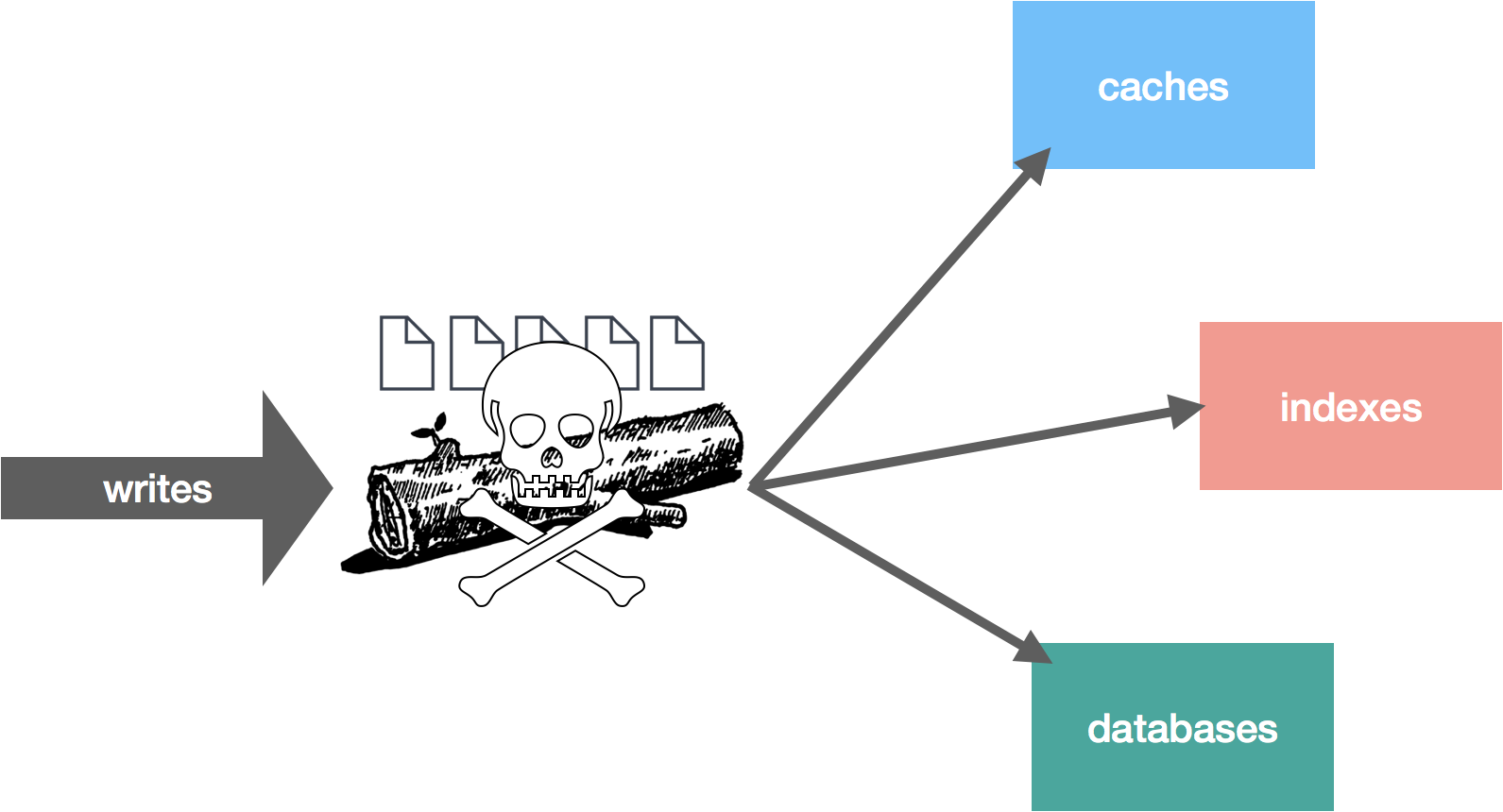

We have our log. We know how to write data to it and read it back as well as how data is persisted. The caveat to this is, although we have a durable log, it’s a single point of failure (SPOF). If the machine where the log data is stored dies, we’re SOL. Recall that one of our three priorities with this system is high availability, so the question is how do we achieve high availability and fault tolerance?

With high availability, we’re specifically talking about ensuring continuity of reads and writes. A server failing shouldn’t preclude either of these, or at least unavailability should be kept to an absolute minimum and without the need for operator intervention. Ensuring this continuity should be fairly obvious: we eliminate the SPOF. To do that, we replicate the data. Replication can also be a means for increasing scalability, but for now we’re only looking at this through the lens of high availability.

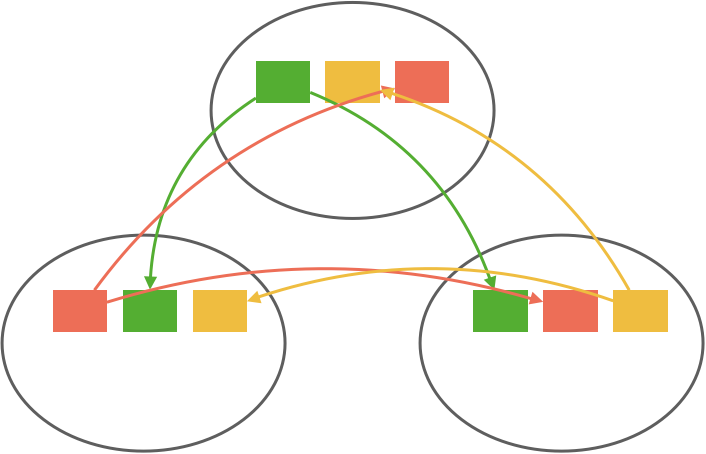

There are a number of ways we can go about replicating the log data. Broadly speaking, we can group the techniques into two different categories: gossip/multicast protocols and consensus protocols. The former includes things like epidemic broadcast trees, bimodal multicast, SWIM, HyParView, and NeEM. These tend to be eventually consistent and/or stochastic. The latter, which I’ve described in more detail here, includes 2PC/3PC, Paxos, Raft, Zab, and chain replication. These tend to favor strong consistency over availability.

So there are a lot of ways we can replicate data, but some of these solutions are better suited than others to this particular problem. Since ordering is an important property of a log, consistency becomes important for a replicated log. If we read from one replica and then read from another, it’s important those views of the log don’t conflict with each other. This more or less rules out the stochastic and eventually consistent options, leaving us with consensus-based replication.

There are essentially two components to consensus-based replication schemes: 1) designate a leader who is responsible for sequencing writes and 2) replicate the writes to the rest of the cluster.

Designating a leader can be as simple as a configuration setting, but the purpose of replication is fault tolerance. If our configured leader crashes, we’re no longer able to accept writes. This means we need the leader to be dynamic. It turns out leader election is a well-understood problem, so we’ll get to this in a bit.

Once a leader is established, it needs to replicate the data to followers. In general, this can be done by either waiting for all replicas or waiting for only a quorum (majority) of replicas. There are pros and cons to both approaches.

| Pros | Cons | |

| All Replicas | Tolerates f failures with f+1 replicas | Latency pegged to slowest replica |

| Quorum | Hides delay from a slow replica | Tolerates f failures with 2f+1 replicas |

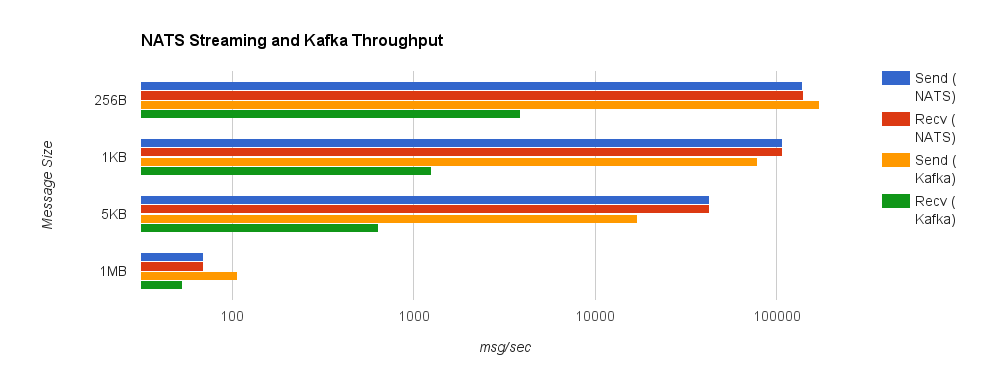

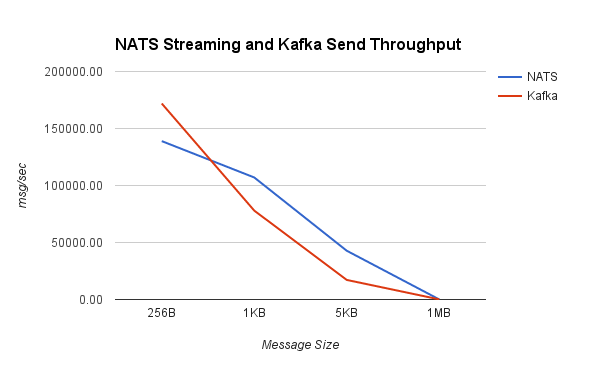

Waiting on all replicas means we can make progress as long as at least one replica is available. With quorum, tolerating the same amount of failures requires more replicas because we need a majority to make progress. The trade-off is that the quorum hides any delays from a slow replica. Kafka is an example of a system which uses all replicas (with some conditions on this which we will see later), and NATS Streaming is one that uses a quorum. Let’s take a look at both in more detail.

Replication in Kafka

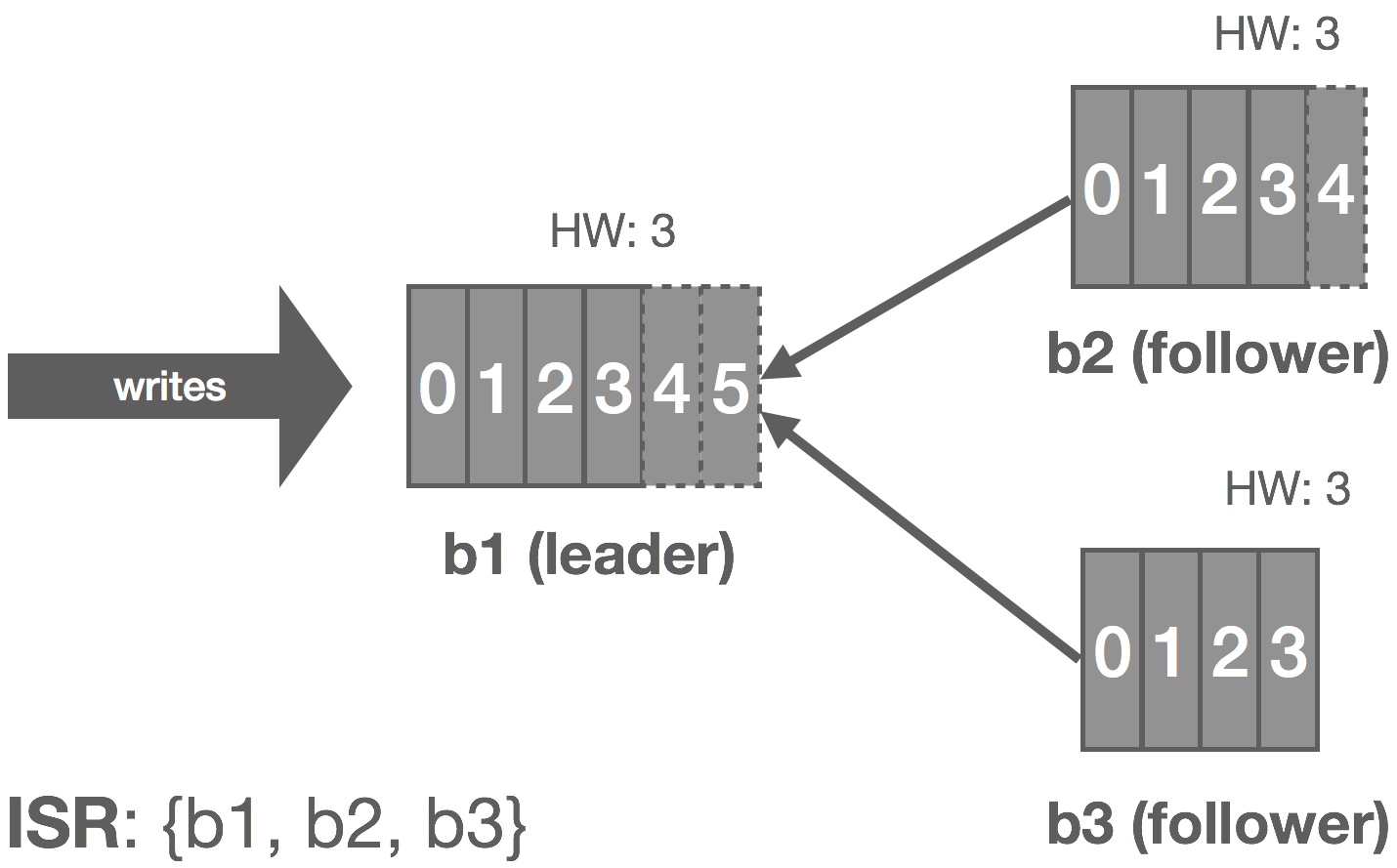

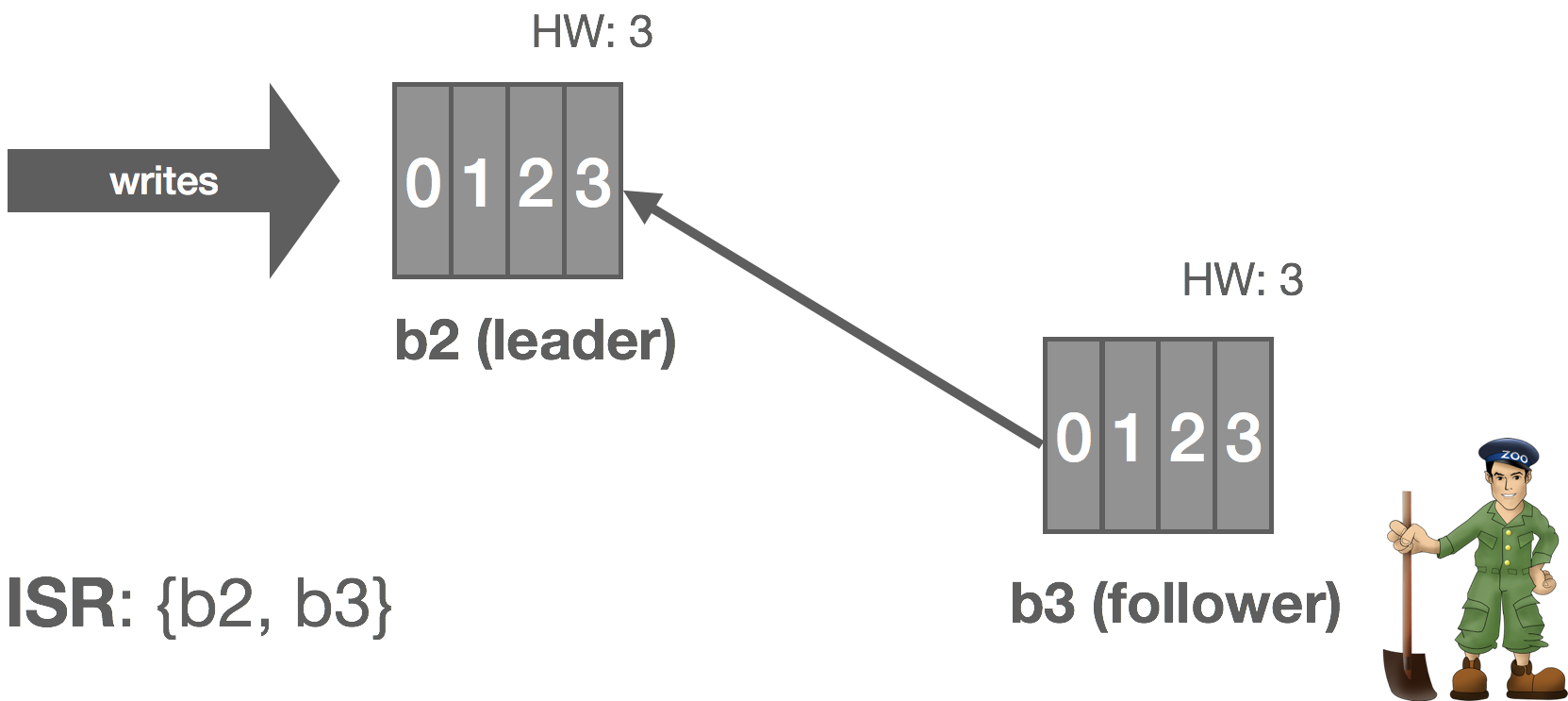

In Kafka, a leader is selected (we’ll touch on this in a moment). This leader maintains an in-sync replica set (ISR) consisting of all the replicas which are fully caught up with the leader. This is every replica, by definition, at the beginning. All reads and writes go through the leader. The leader writes messages to a write-ahead log (WAL). Messages written to the WAL are considered uncommitted or “dirty” initially. The leader only commits a message once all replicas in the ISR have written it to their own WAL. The leader also maintains a high-water mark (HW) which is the last committed message in the WAL. This gets piggybacked on the replica fetch responses from which replicas periodically checkpoint to disk for recovery purposes. The piggybacked HW then allows replicas to know when to commit.

Only committed messages are exposed to consumers. However, producers can configure how they want to receive acknowledgements on writes. It can wait until the message is committed on the leader (and thus replicated to the ISR), wait for the message to only be written (but not committed) to the leader’s WAL, or not wait at all. This all depends on what trade-offs the producer wants to make between latency and durability.

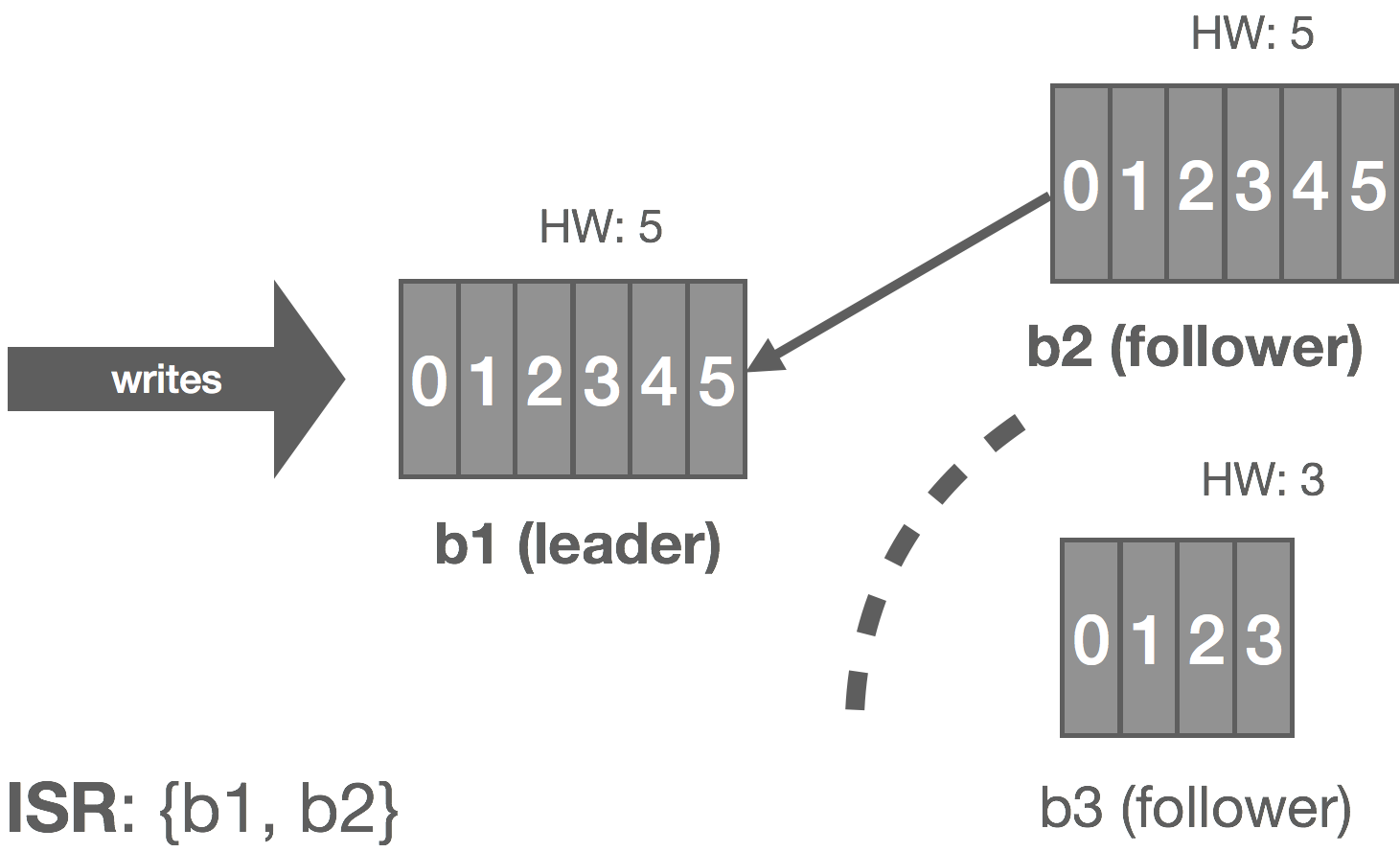

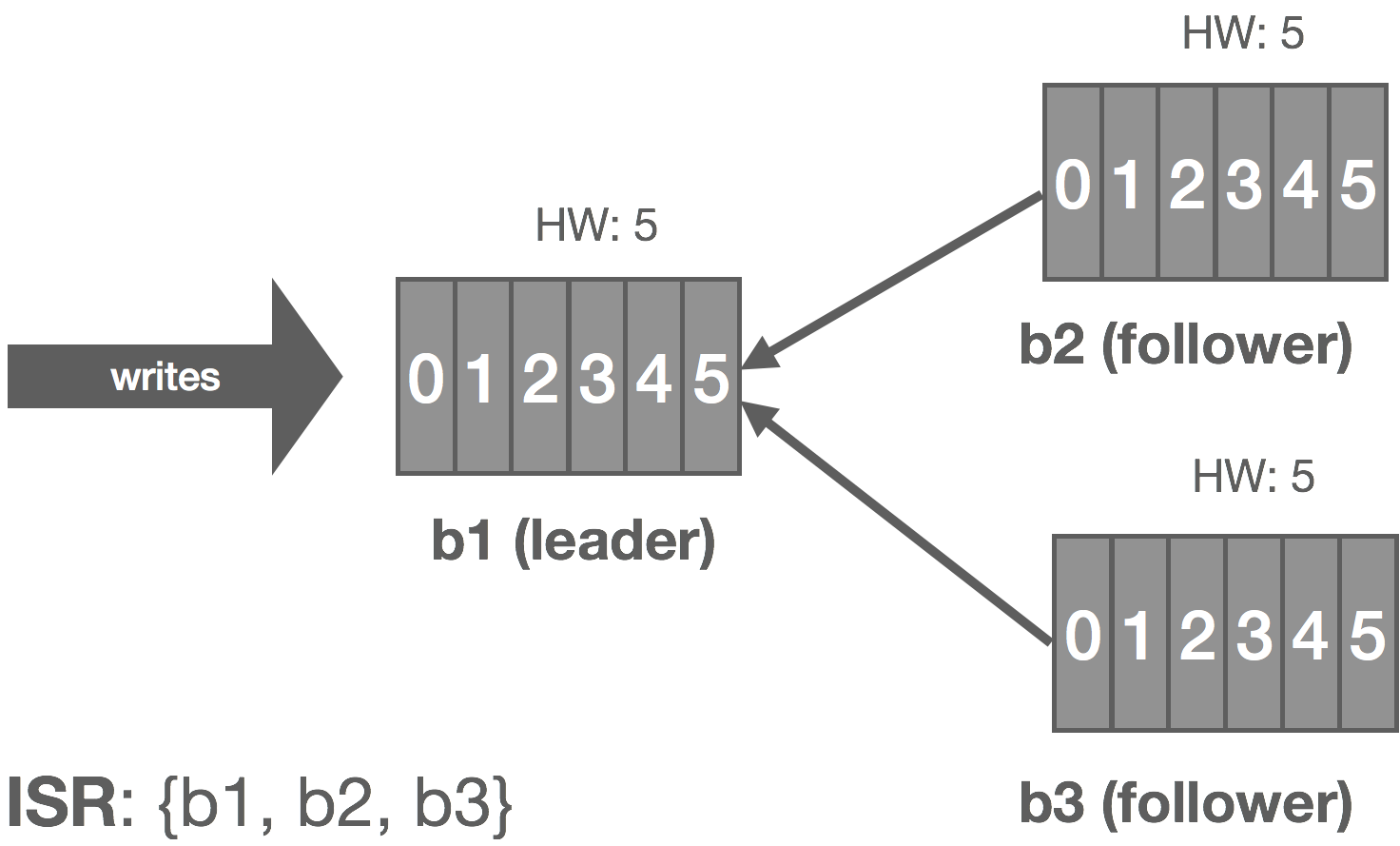

The graphic below shows how this replication process works for a cluster of three brokers: b1, b2, and b3. Followers are effectively special consumers of the leader’s log.

Now let’s look at a few failure modes and how Kafka handles them.

Leader Fails

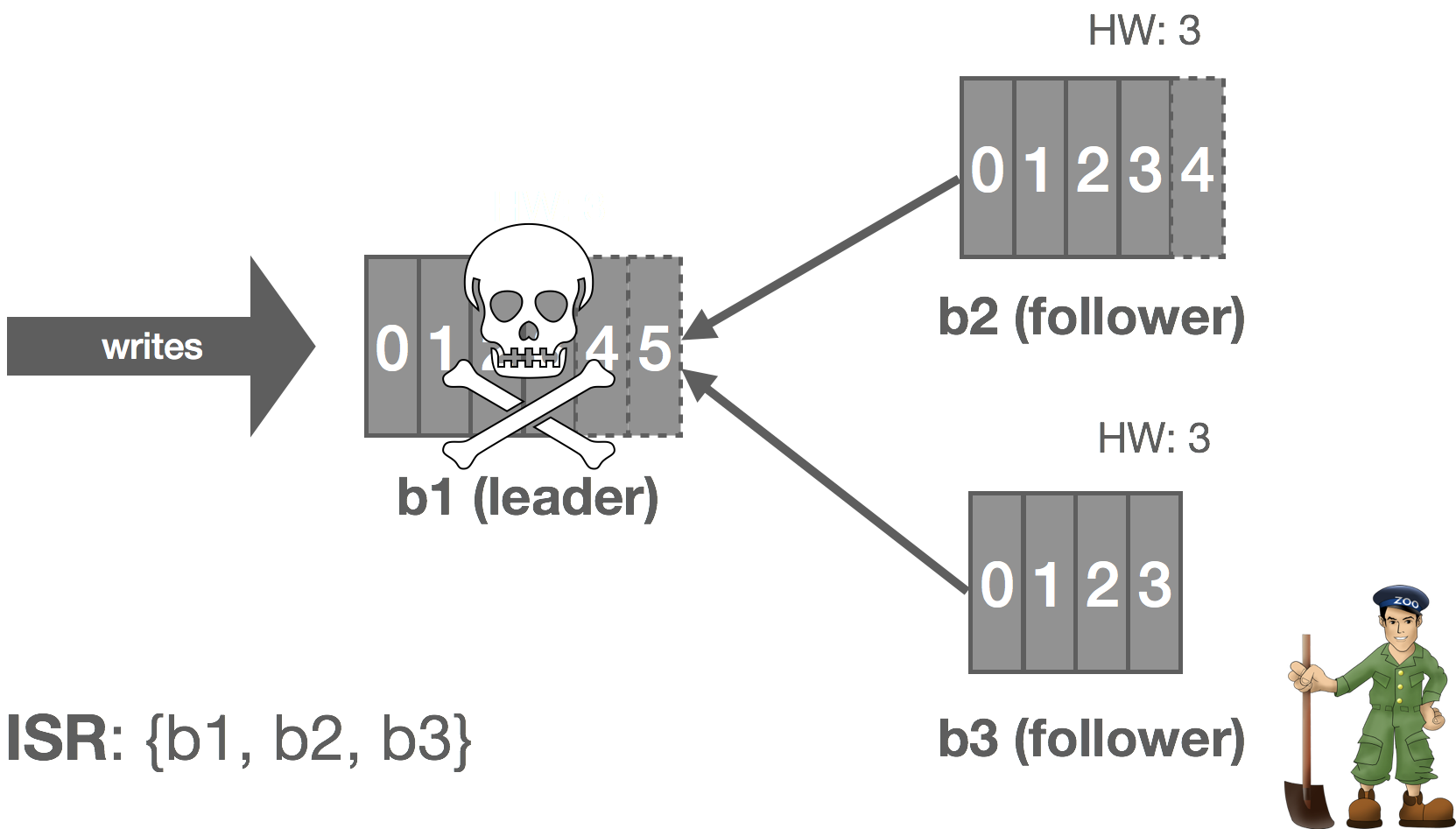

Kafka relies on Apache ZooKeeper for certain cluster coordination tasks, such as leader election, though this is not actually how the log leader is elected. A Kafka cluster has a single controller broker whose election is handled by ZooKeeper. This controller is responsible for performing administrative tasks on the cluster. One of these tasks is selecting a new log leader (actually partition leader, but this will be described later in the series) from the ISR when the current leader dies. ZooKeeper is also used to detect these broker failures and signal them to the controller.

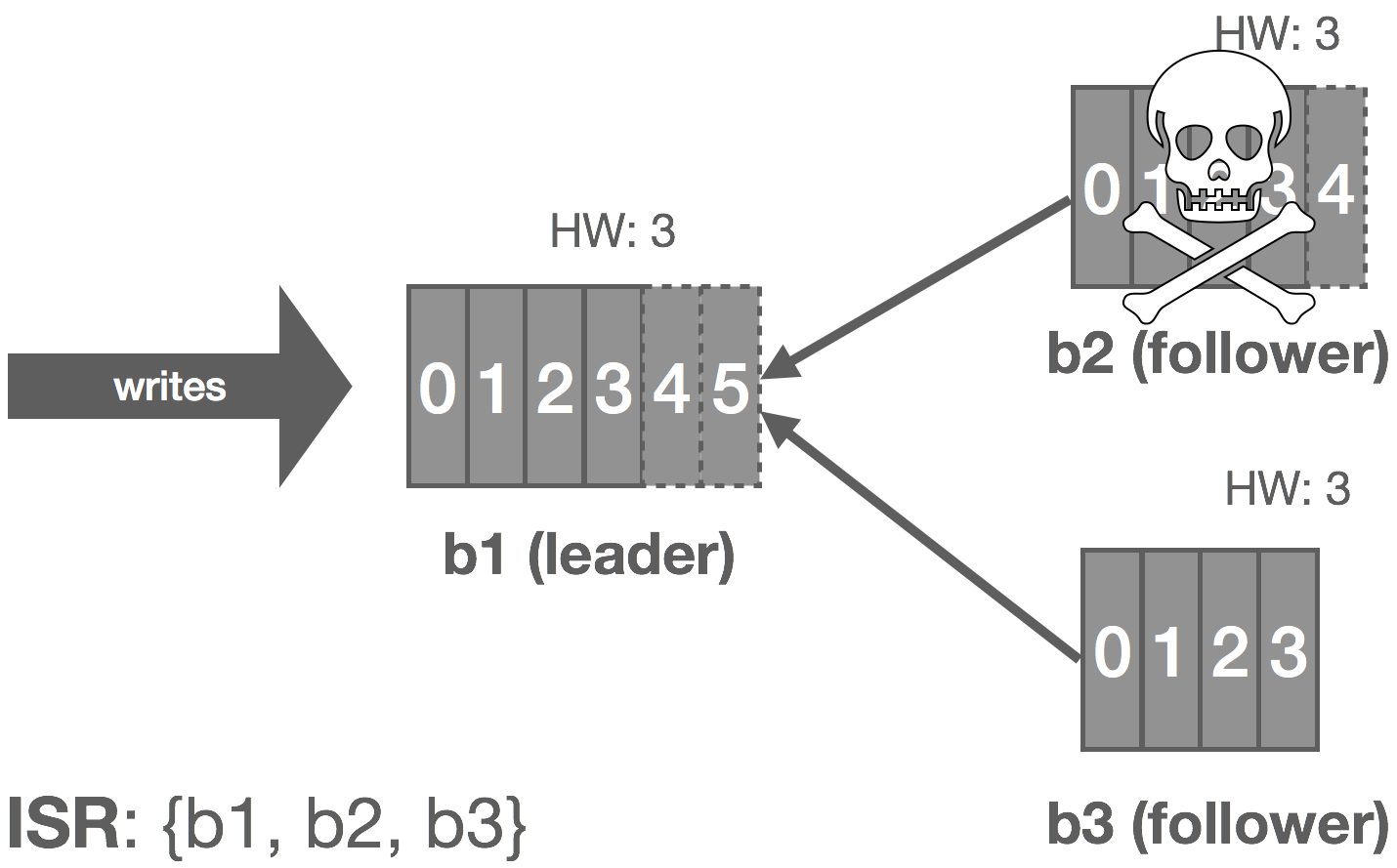

Thus, when the leader crashes, the cluster controller is notified by ZooKeeper and it selects a new leader from the ISR and announces this to the followers. This gives us automatic failover of the leader. All committed messages up to the HW are preserved and uncommitted messages may be lost during the failover. In this case, b1 fails and b2 steps up as leader.

Follower Fails

The leader tracks information on how “caught up” each replica is. Before Kafka 0.9, this included both how many messages a replica was behind, replica.lag.max.messages, and the amount of time since the replica last fetched messages from the leader, replica.lag.time.max.ms. Since 0.9, replica.lag.max.messages was removed and replica.lag.time.max.ms now refers to both the time since the last fetch request and the amount of time since the replica last caught up.

Thus, when a follower fails (or stops fetching messages for whatever reason), the leader will detect this based on replica.lag.time.max.ms. After that time expires, the leader will consider the replica out of sync and remove it from the ISR. In this scenario, the cluster enters an “under-replicated” state since the ISR has shrunk. Specifically, b2 fails and is removed from the ISR.

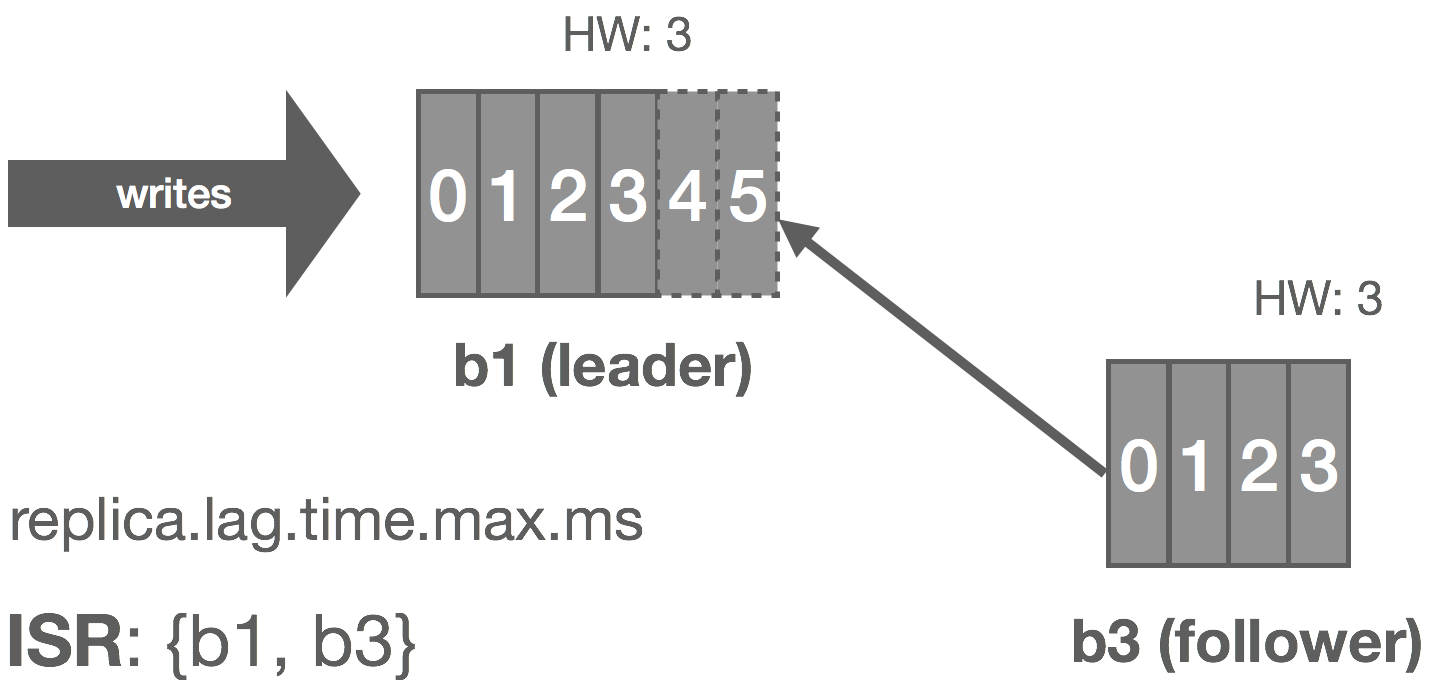

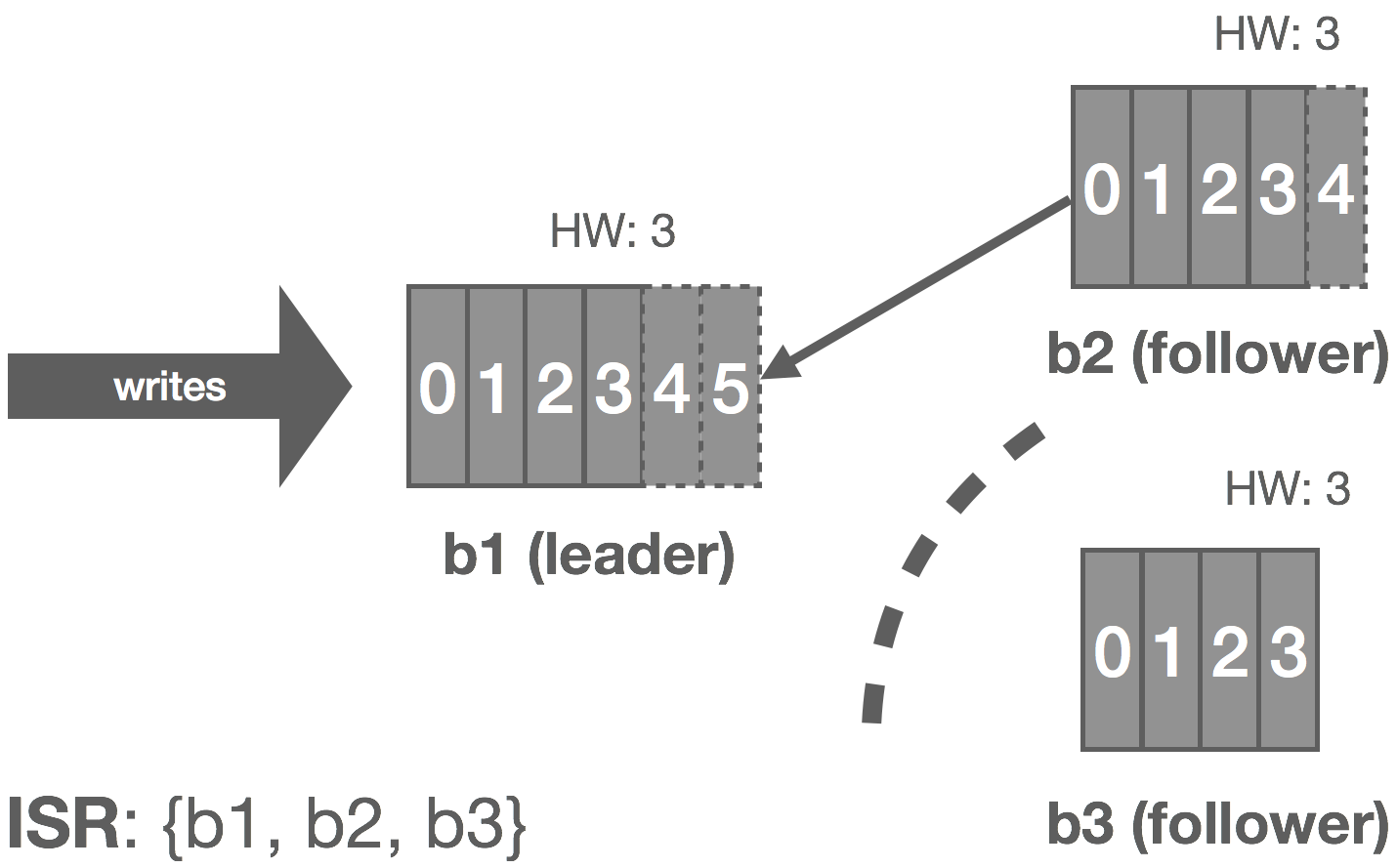

Follower Temporarily Partitioned

The case of a follower being temporarily partitioned, e.g. due to a transient network failure, is handled in a similar fashion to the follower itself failing. These two failure modes can really be combined since the latter is just the former with an arbitrarily long partition, i.e. it’s the difference between crash-stop and crash-recovery models.

In this case, b3 is partitioned from the leader. As before, replica.lag.time.max.ms acts as our failure detector and causes b3 to be removed from the ISR. We enter an under-replicated state and the remaining two brokers continue committing messages 4 and 5. Accordingly, the HW is updated to 5 on these brokers.

When the partition heals, b3 continues reading from the leader and catching up. Once it is fully caught up with the leader, it’s added back into the ISR and the cluster resumes its fully replicated state.

We can generalize this to the crash-recovery model. For example, instead of a network partition, the follower could crash and be restarted later. When the failed replica is restarted, it recovers the HW from disk and truncates its log up to the HW. This preserves the invariant that messages after the HW are not guaranteed to be committed. At this point, it can begin catching up from the leader and will end up with a log consistent with the leader’s once fully caught up.

Replication in NATS Streaming

NATS Streaming relies on the Raft consensus algorithm for leader election and data replication. This sometimes comes as a surprise to some as Raft is largely seen as a protocol for replicated state machines. We’ll try to understand why Raft was chosen for this particular problem in the following sections. We won’t dive deep into Raft itself beyond what is needed for the purposes of this discussion.

While a log is a state machine, it’s a very simple one: a series of appends. Raft is frequently used as the replication mechanism for key-value stores which have a clearer notion of “state machine.” For example, with a key-value store, we have set and delete operations. If we set foo = bar and then later set foo = baz, the state gets rolled up. That is, we don’t necessarily care about the provenance of the key, only its current state.

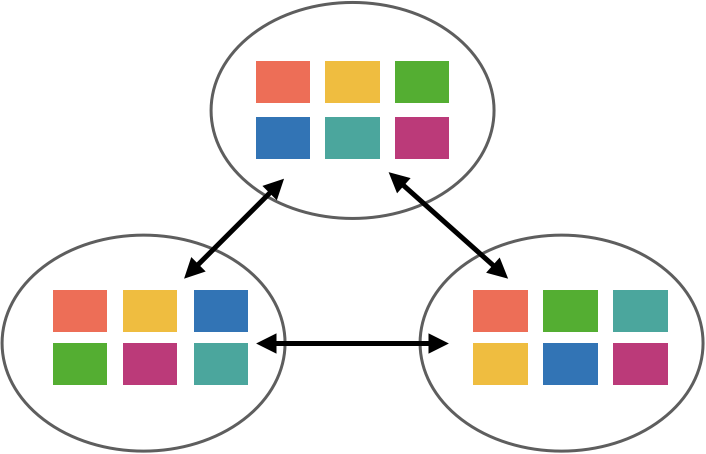

However, NATS Streaming differs from Kafka in a number of key ways. One of these differences is that NATS Streaming attempts to provide a sort of unified API for streaming and queueing semantics not too dissimilar from Apache Pulsar. This means, while it has a notion of a log, it also has subscriptions on that log. Unlike Kafka, NATS Streaming tracks these subscriptions and metadata associated with them, such as where a client is in the log. These have definite “state machines” affiliated with them, like creating and deleting subscriptions, positions in the log, clients joining or leaving queue groups, and message-redelivery information.

Currently, NATS Streaming uses multiple Raft groups for replication. There is a single metadata Raft group used for replicating client state and there is a separate Raft group per topic which replicates messages and subscriptions.

Raft solves both the problems of leader election and data replication in a single protocol. The Secret Lives of Data provides an excellent interactive illustration of how this works. As you step through that illustration, you’ll notice that the algorithm is actually quite similar to the Kafka replication protocol we walked through earlier. This is because although Raft is used to implement replicated state machines, it actually is a replicated WAL, which is exactly what Kafka is. One benefit of using Raft is we no longer have the need for ZooKeeper or some other coordination service.

Raft handles electing a leader. Heartbeats are used to maintain leadership. Writes flow through the leader to the followers. The leader appends writes to its WAL and they are subsequently piggybacked onto the heartbeats which get sent to the followers using AppendEntries messages. At this point, the followers append the write to their own WALs, assuming they don’t detect a gap, and send a response back to the leader. The leader commits the write once it receives a successful response from a quorum of followers.

Similar to Kafka, each replica in Raft maintains a high-water mark of sorts called the commit index, which is the index of the highest log entry known to be committed. This is piggybacked on the AppendEntries messages which the followers use to know when to commit entries in their WALs. If a follower detects that it missed an entry (i.e. there was a gap in the log), it rejects the AppendEntries and informs the leader to rewind the replication. The Raft paper details how it ensures correctness, even in the face of many failure modes such as the ones described earlier.

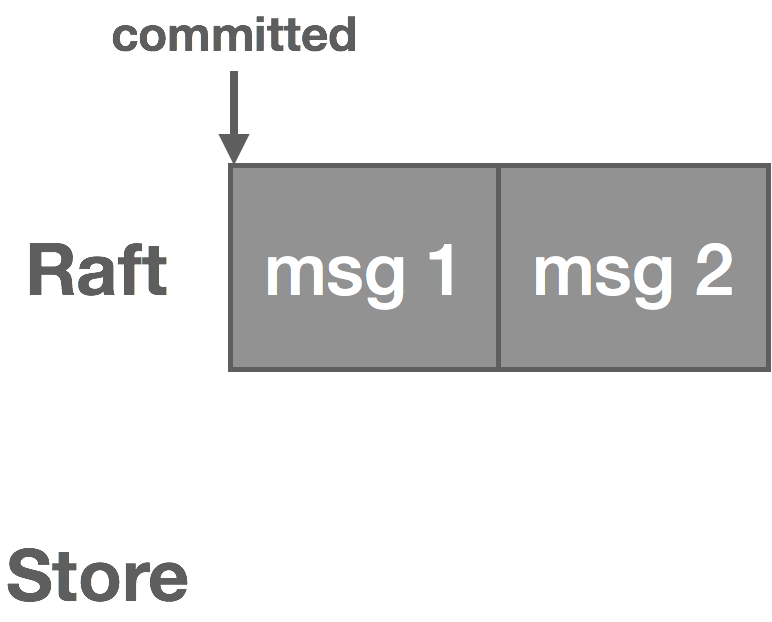

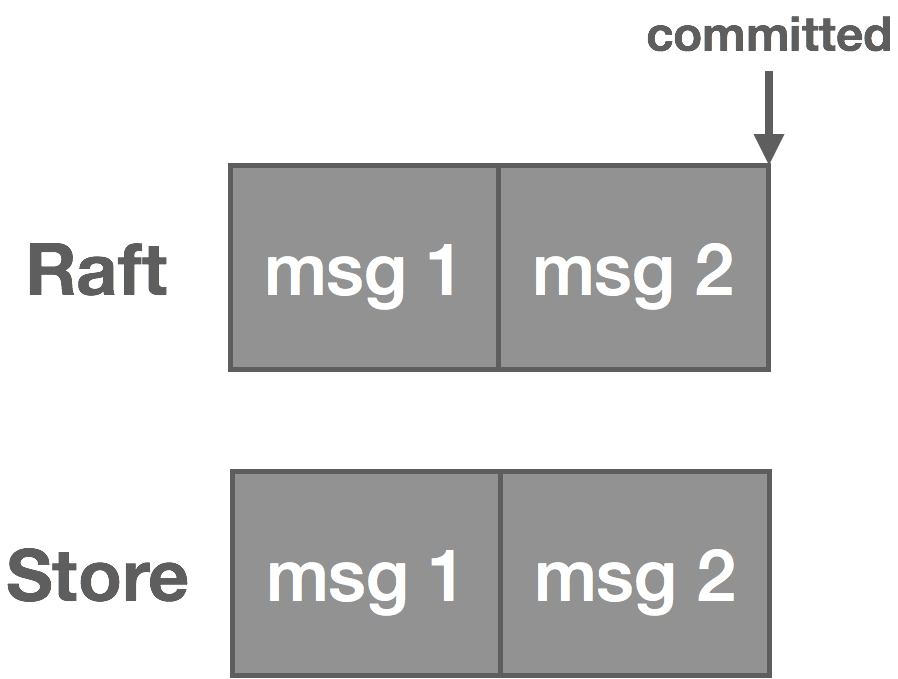

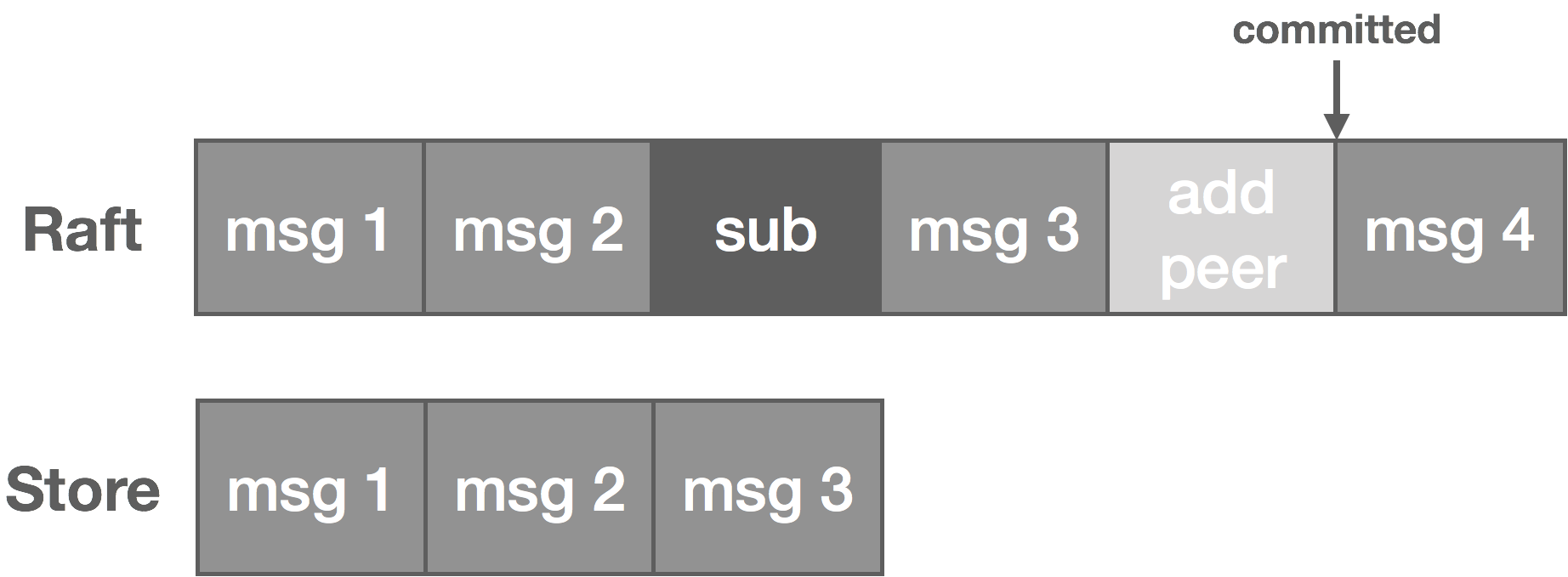

Conceptually, there are two logs: the Raft log and the NATS Streaming message log. The Raft log handles replicating messages and, once committed, they are appended to the NATS Streaming log. If it seems like there’s some redundancy here, that’s because there is, which we’ll get to soon. However, keep in mind we’re not just replicating the message log, but also the state machines associated with the log and any clients.

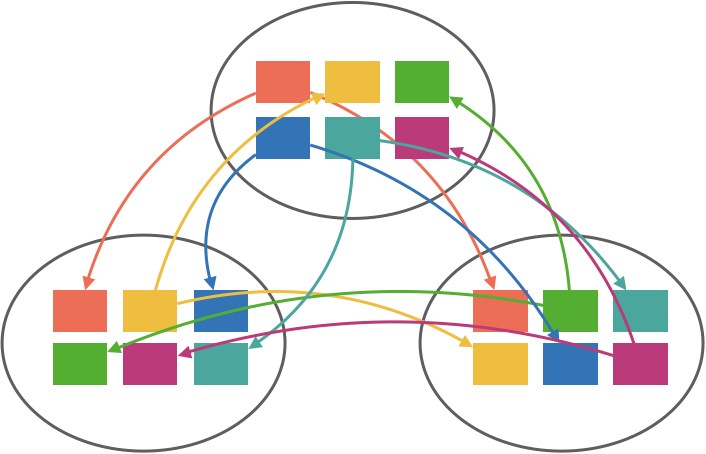

There are a few challenges with this replication technique, two of which we will talk about. The first is scaling Raft. With a single topic, there is one Raft group, which means one node is elected leader and it heartbeats messages to followers.

As the number of topics increases, so do the number of Raft groups, each with their own leaders and heartbeats. Unless we constrain the Raft group participants or the number of topics, this creates an explosion of network traffic between nodes.

There are a couple ways we can go about addressing this. One option is to run a fixed number of Raft groups and use a consistent hash to map a topic to a group. This can work well if we know roughly the number of topics beforehand since we can size the number of Raft groups accordingly. If you expect only 10 topics, running 10 Raft groups is probably reasonable. But if you expect 10,000 topics, you probably don’t want 10,000 Raft groups. If hashing is consistent, it would be feasible to dynamically add or remove Raft groups at runtime, but it would still require repartitioning a portion of topics which can be complicated.

Another option is to run an entire node’s worth of topics as a single group using a layer on top of Raft. This is what CockroachDB does to scale Raft in proportion to the number of key ranges using a layer on top of Raft they call MultiRaft. This requires some cooperation from the Raft implementation, so it’s a bit more involved than the partitioning technique but eschews the repartitioning problem and redundant heartbeating.

The second challenge with using Raft for this problem is the issue of “dual writes.” As mentioned before, there are really two logs: the Raft log and the NATS Streaming message log, which we’ll call the “store.” When a message is published, the leader writes it to its Raft log and it goes through the Raft replication process.

Once the message is committed in Raft, it’s written to the NATS Streaming log and the message is now visible to consumers.

Note, however, that not only messages are written to the Raft log. We also have subscriptions and cluster topology changes, for instance. These other items are not written to the NATS Streaming log but handled in other ways on commit. That said, messages tend to occur in much greater volume than these other entries.

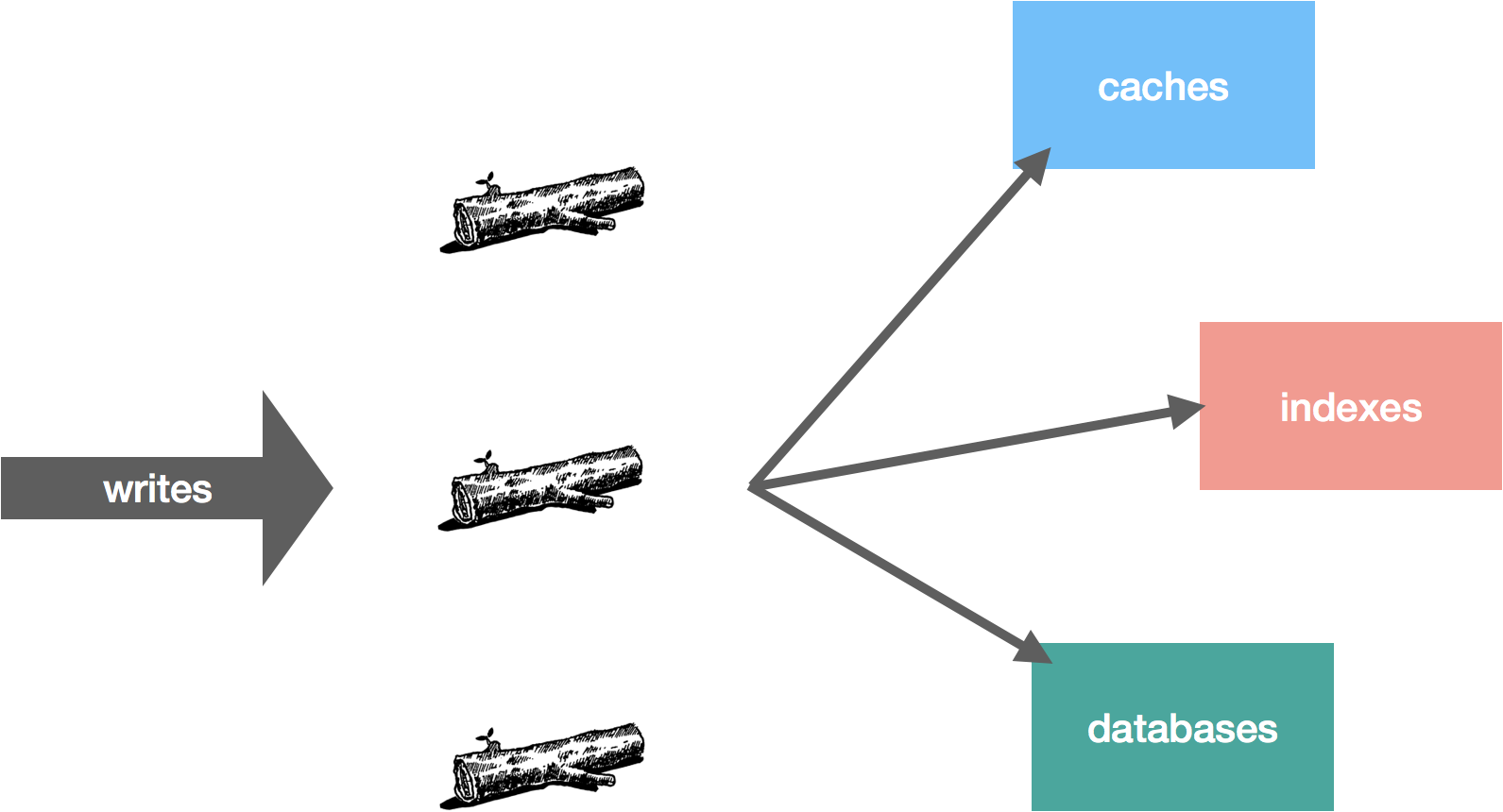

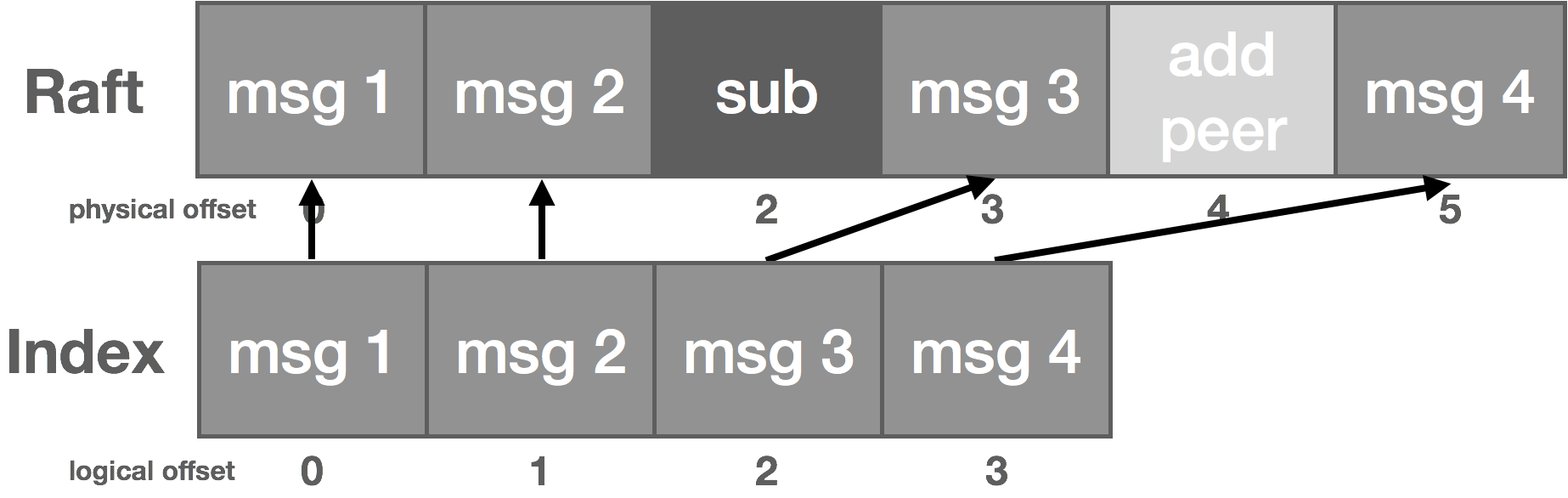

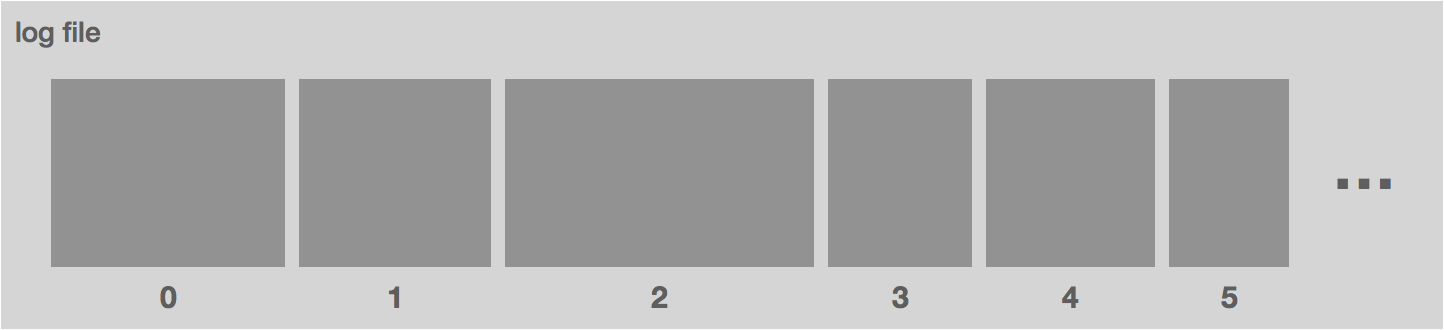

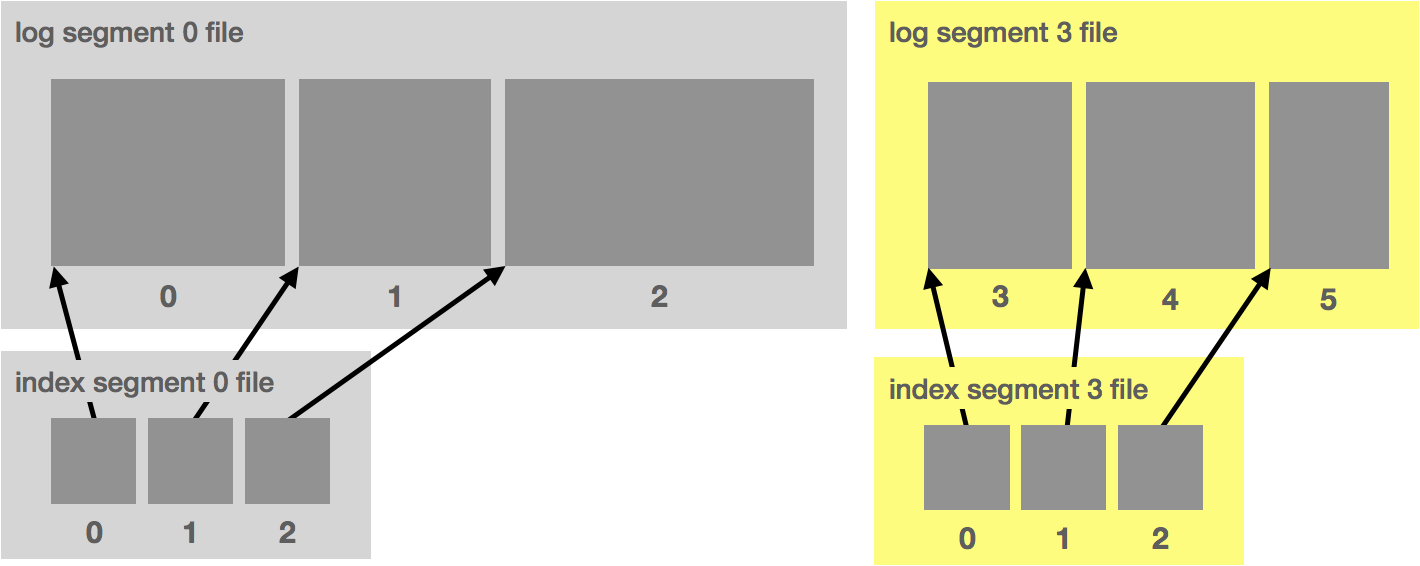

Messages end up getting stored redundantly, once in the Raft log and once in the NATS Streaming log. We can address this problem if we think about our logs a bit differently. If you recall from part one, our log storage consists of two parts: the log segment and the log index. The segment stores the actual log data, and the index stores a mapping from log offset to position in the segment.

Along these lines, we can think of the Raft log index as a “physical offset” and the NATS Streaming log index as a “logical offset.” Instead of maintaining two logs, we treat the Raft log as our message write-ahead log and treat the NATS Streaming log as an index into that WAL. Particularly, messages are written to the Raft log as usual. Once committed, we write an index entry for the message offset that points back into the log. As before, we use the index to do lookups into the log and can then read sequentially from the log itself.

Remaining Questions

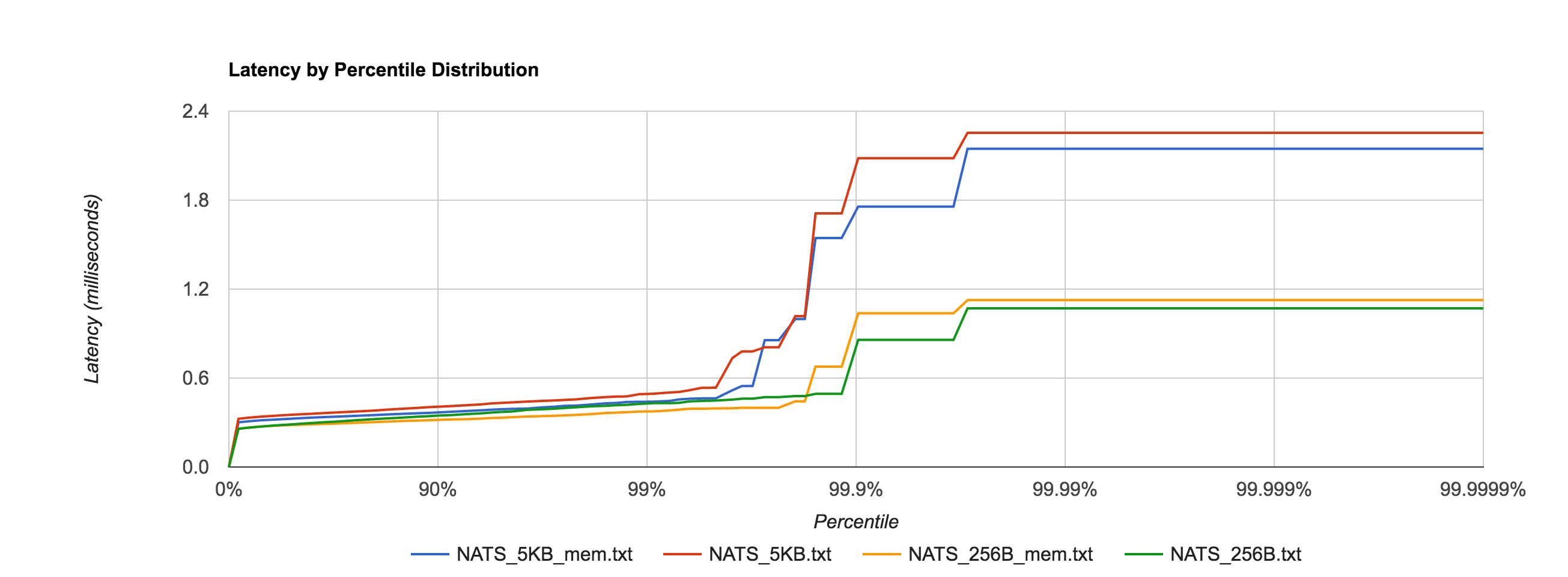

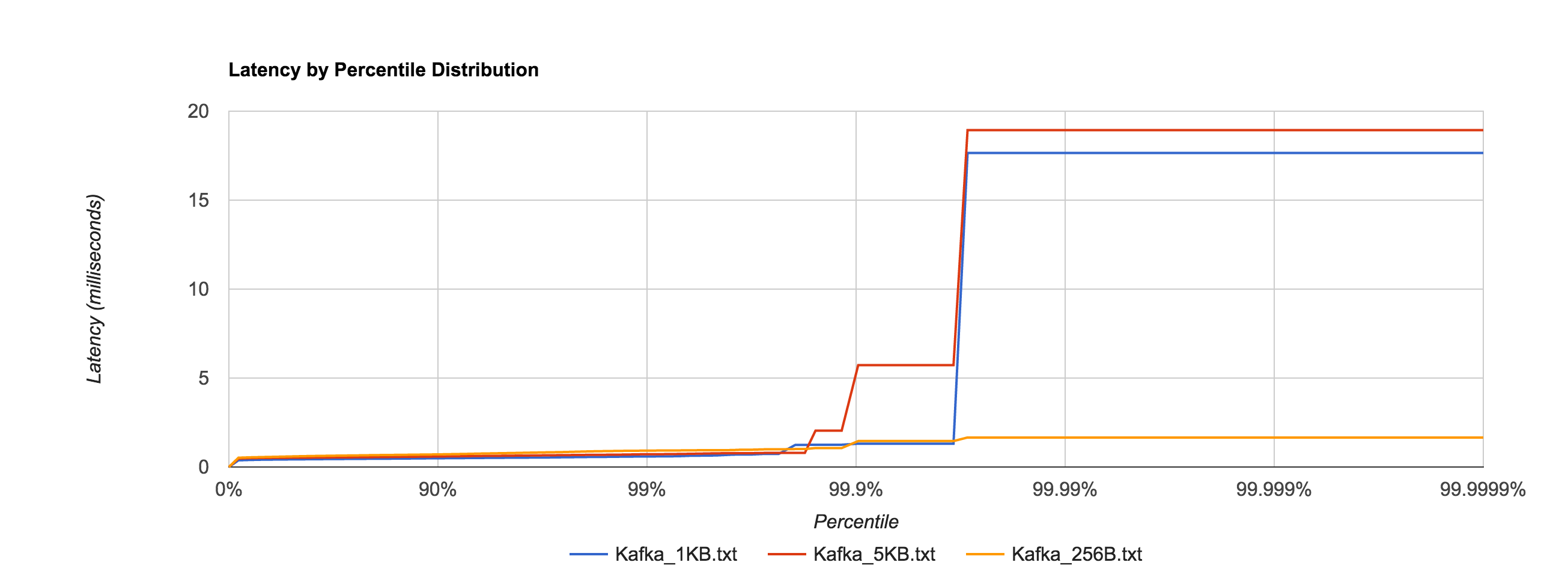

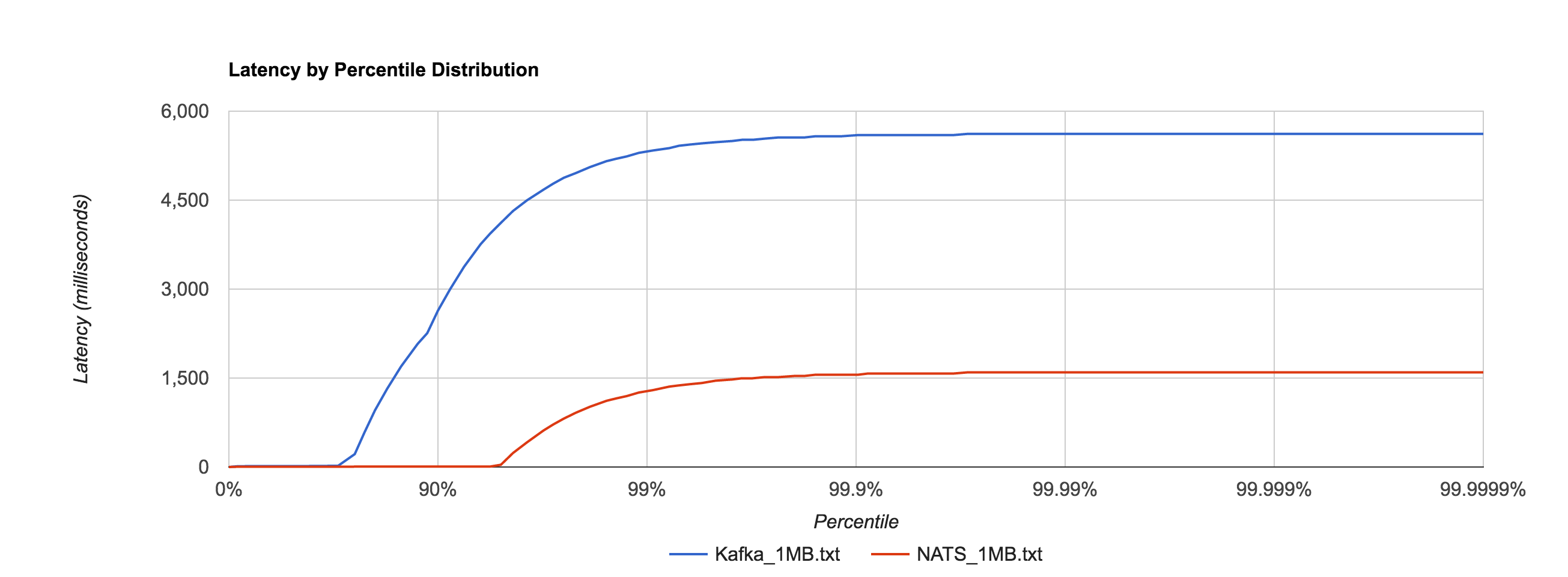

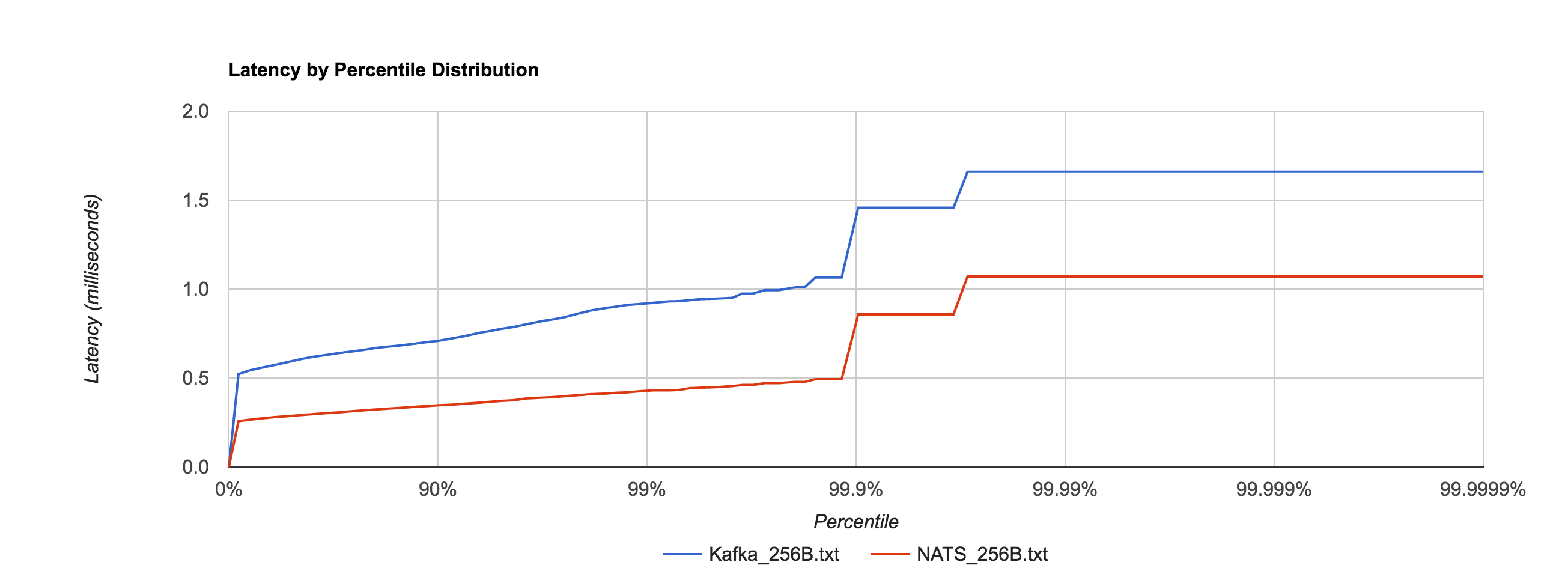

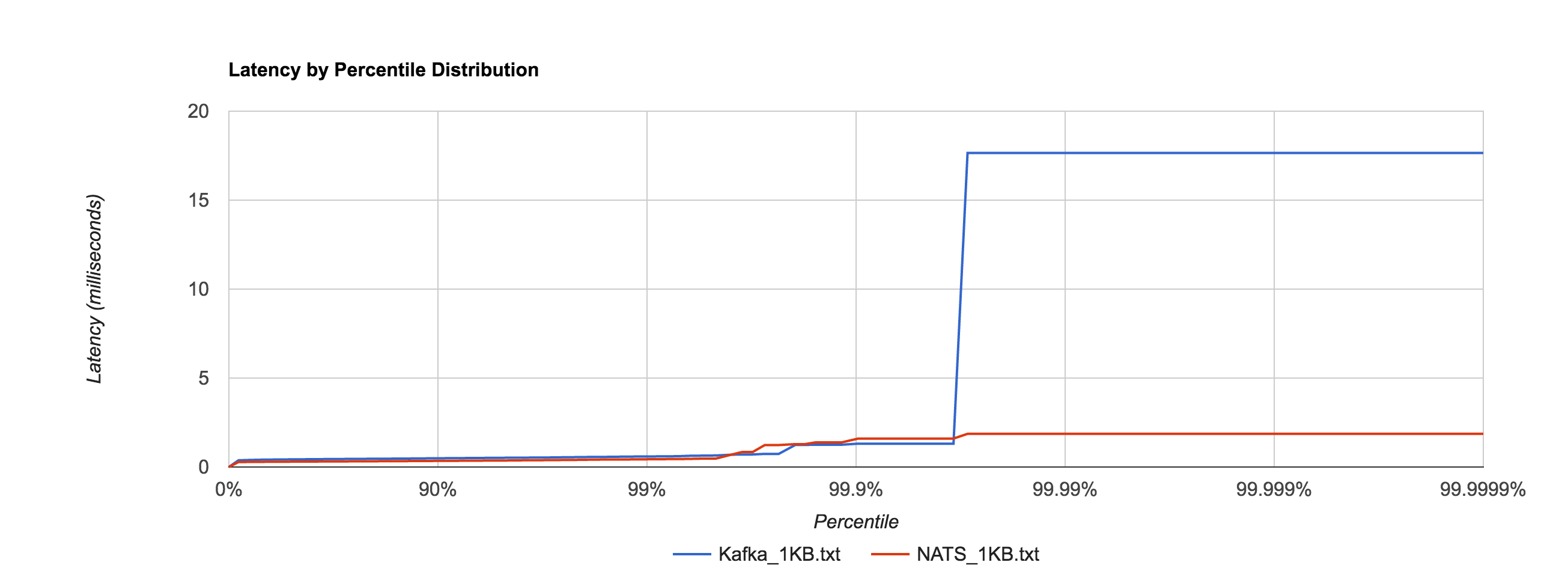

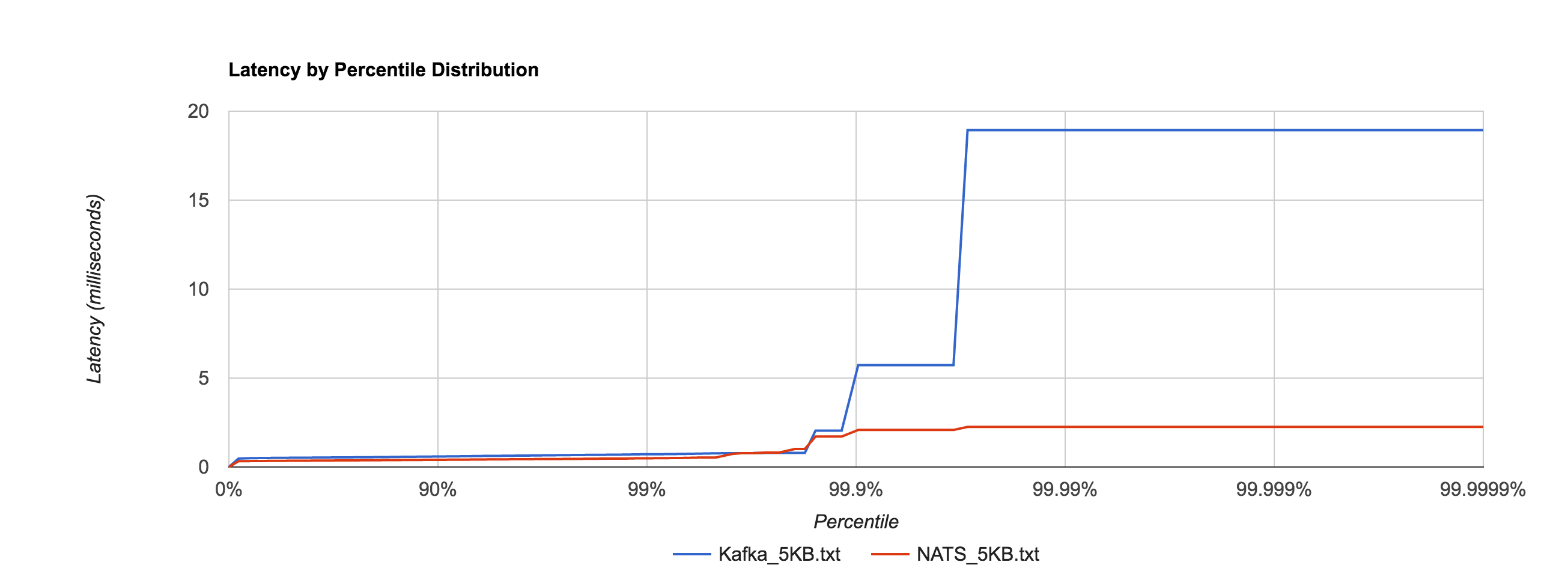

We’ve answered the questions of how to ensure continuity of reads and writes, how to replicate data, and how to ensure replicas are consistent. The remaining two questions pertaining to replication are how do we keep things fast and how do we ensure data is durable?

There are several things we can do with respect to performance. The first is we can configure publisher acks depending on our application’s requirements. Specifically, we have three options. The first is the broker acks on commit. This is slow but safe as it guarantees the data is replicated. The second is the broker acks on appending to its local log. This is fast but unsafe since it doesn’t wait on any replica roundtrips but, by that very fact, means that the data is not replicated. If the leader crashes, the message could be lost. Lastly, the publisher can just not wait for an ack at all. This is the fastest but least safe option for obvious reasons. Tuning this all depends on what requirements and trade-offs make sense for your application.

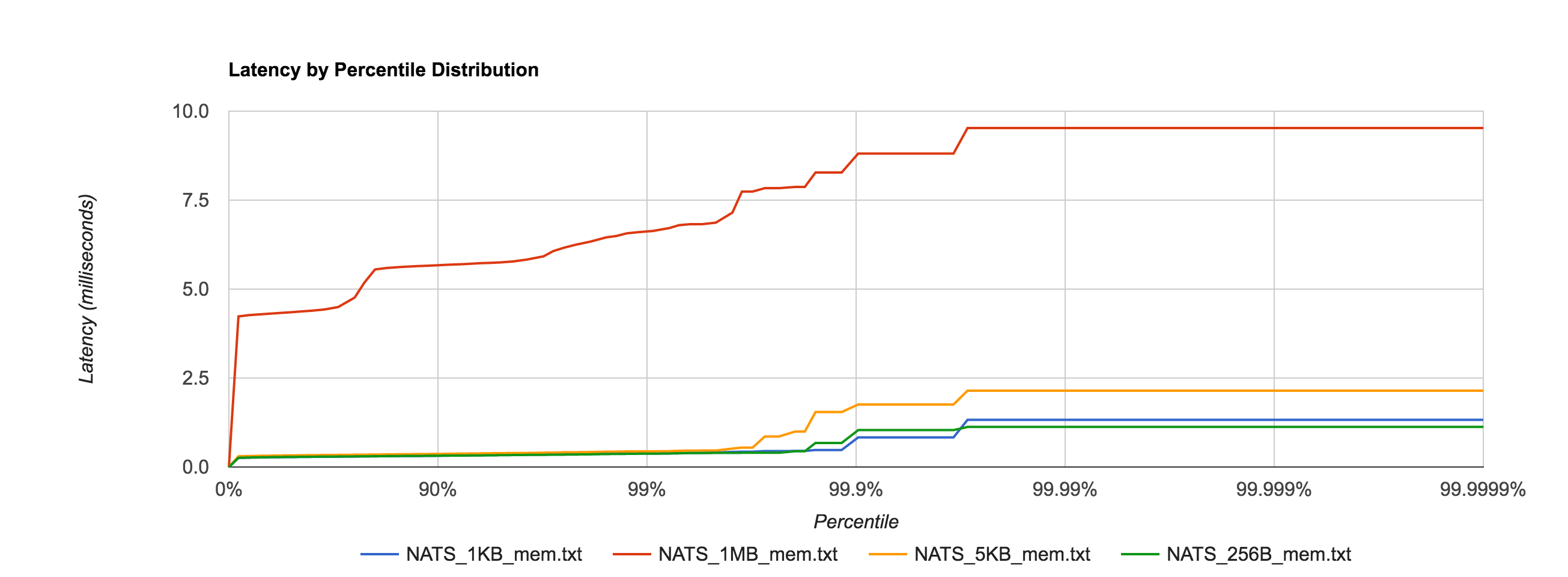

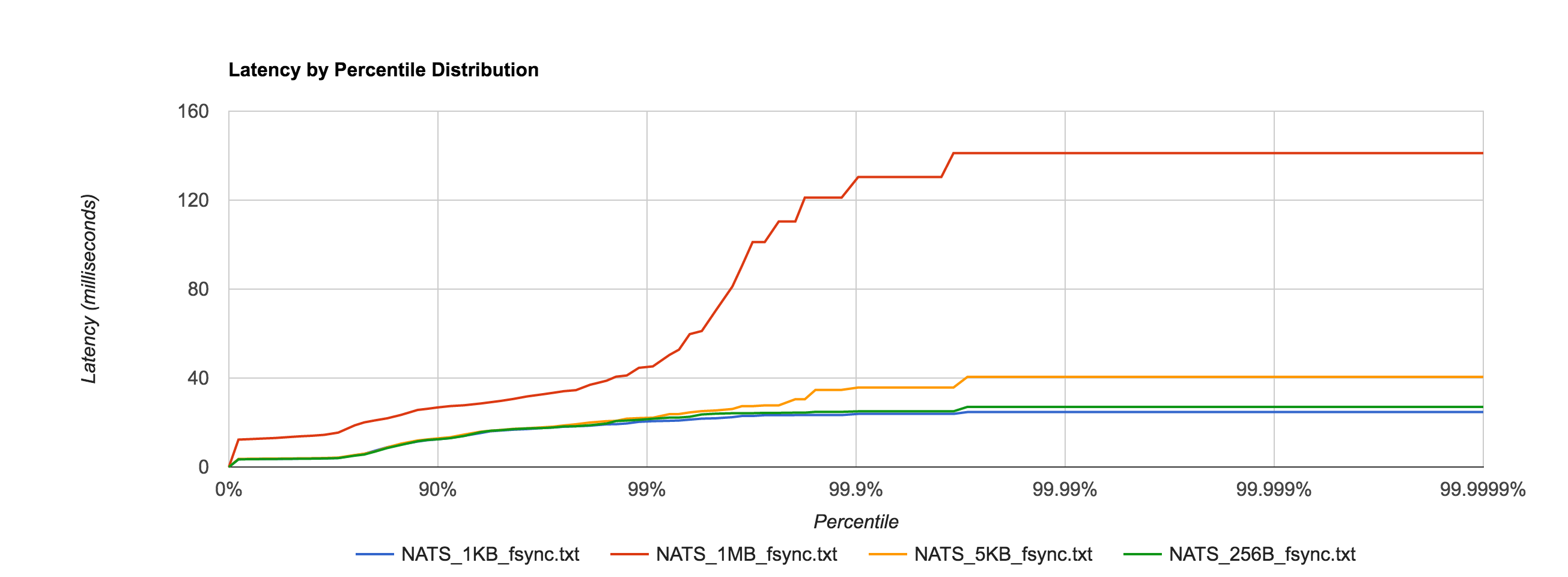

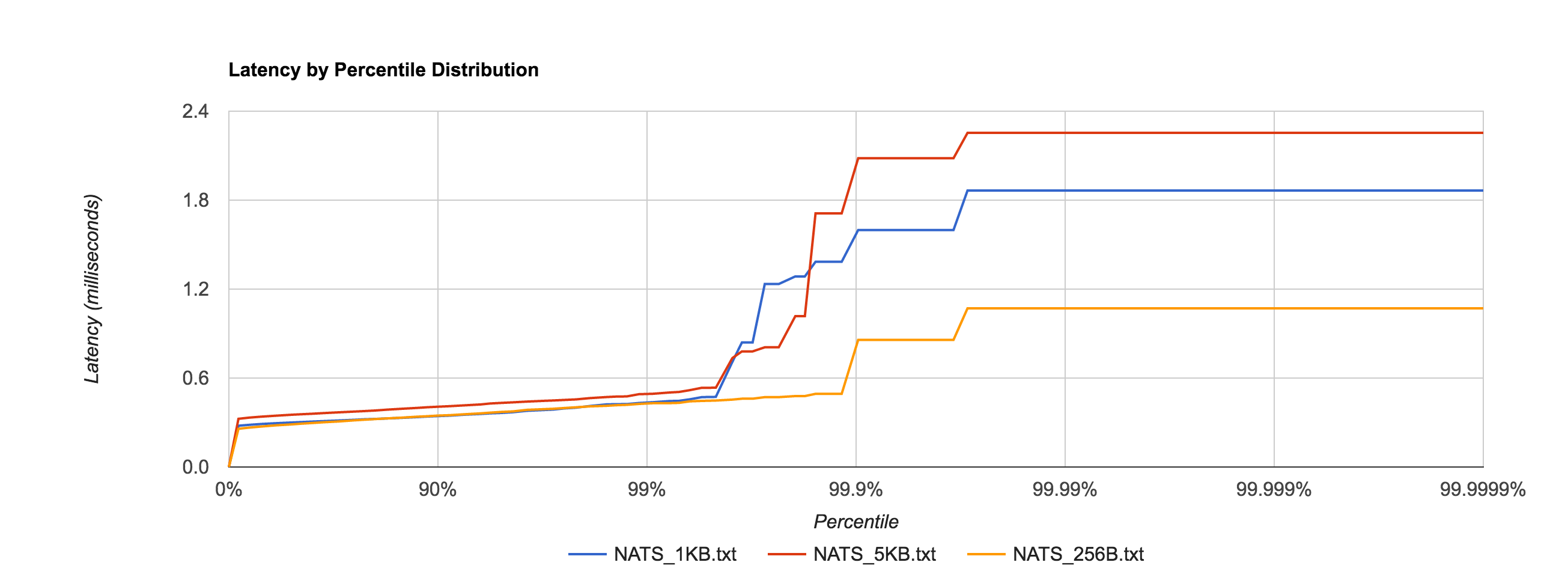

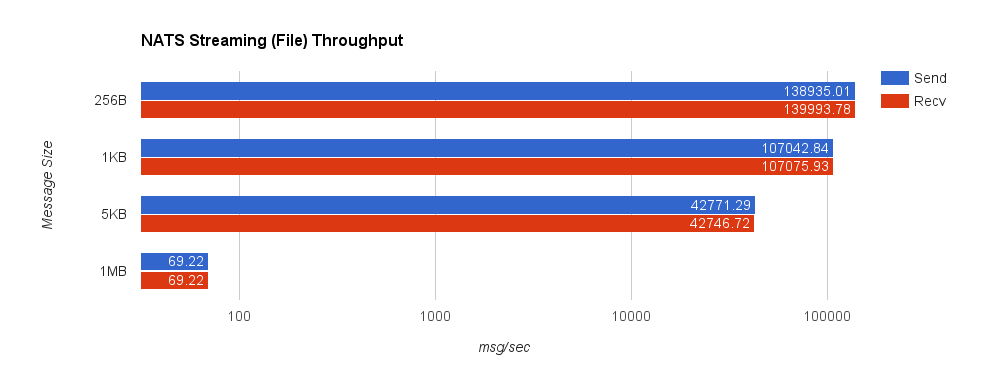

The second thing we do is don’t explicitly fsync writes on the broker and instead rely on replication for durability. Both Kafka and NATS Streaming (when clustered) do this. With fsync enabled (in Kafka, this is configured with flush.messages and/or flush.ms and in NATS Streaming, with file_sync), every message that gets published results in a sync to disk. This ends up being very expensive. The thought here is if we are replicating to enough nodes, the replication itself is sufficient for HA of data since the likelihood of more than a quorum of nodes failing is low, especially if we are using rack-aware clustering. Note that data is still periodically flushed in the background by the kernel.

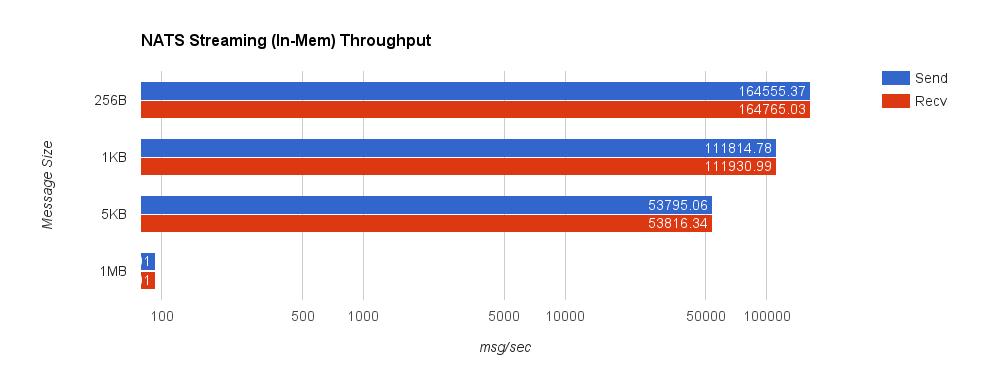

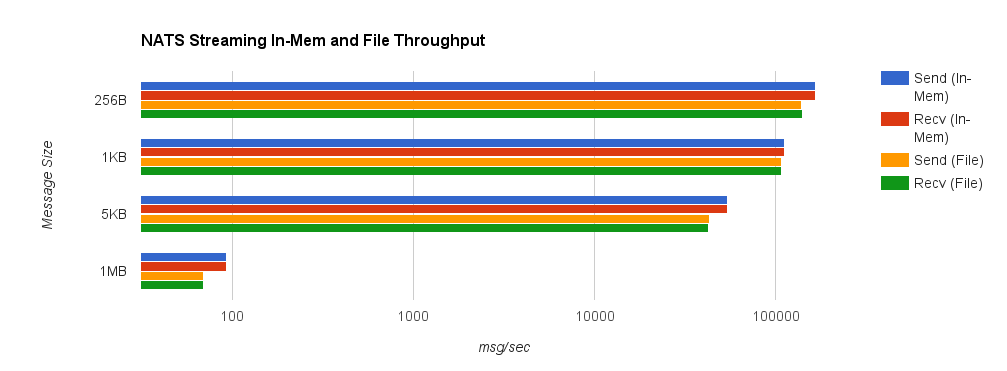

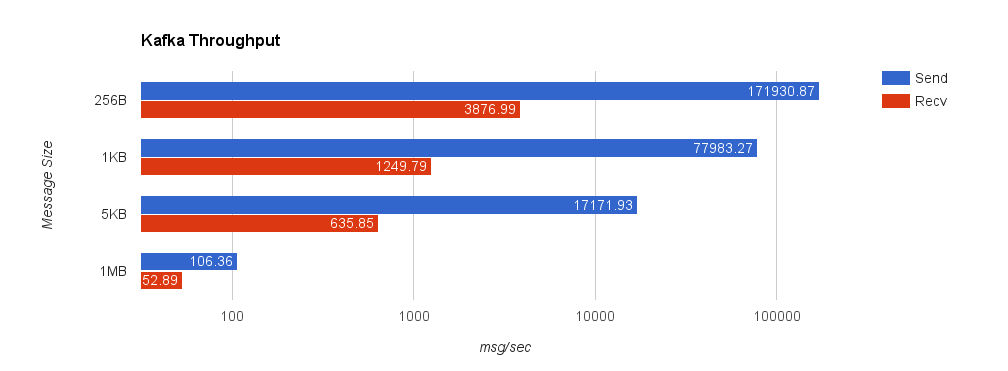

Batching aggressively is also a key part of ensuring good performance. Kafka supports end-to-end batching from the producer all the way to the consumer. NATS Streaming does not currently support batching at the API level, but it uses aggressive batching when replicating and persisting messages. In my experience, this makes about an order-of-magnitude improvement in throughput.

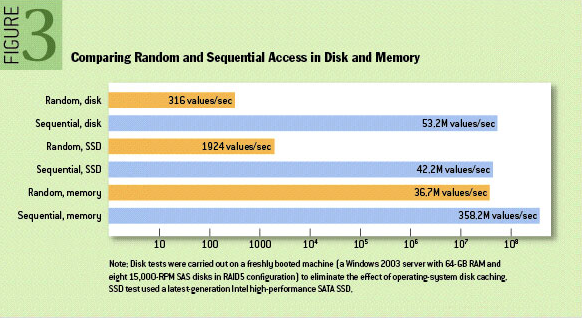

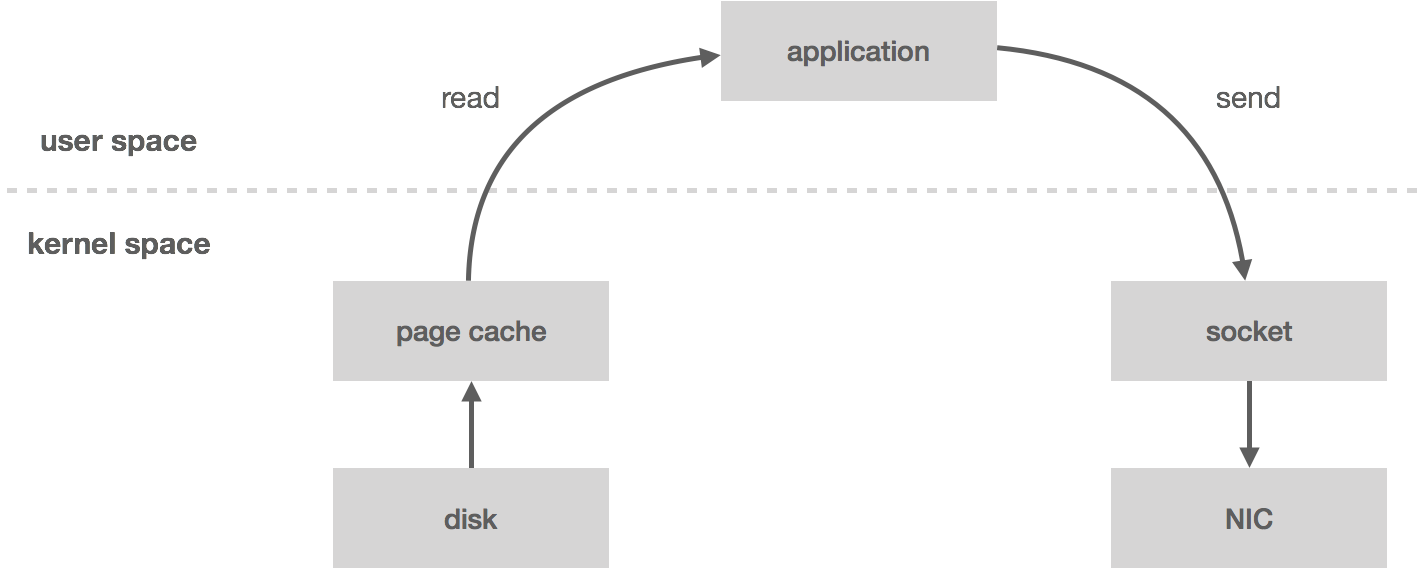

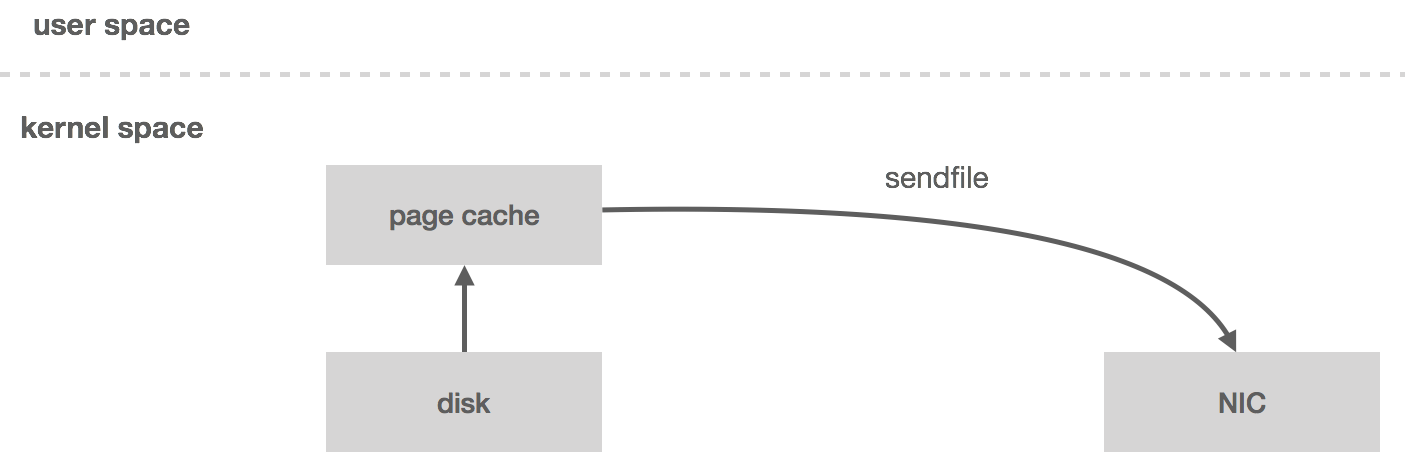

Finally, as already discussed earlier in the series, keeping disk access sequential and maximizing zero-copy reads makes a big difference as well.

There are a few things worth noting with respect to durability. Quorum is what guarantees durability of data. This comes “for free” with Raft due to the nature of that protocol. In Kafka, we need to do a bit of configuring to ensure this. Namely, we need to configure min.insync.replicas on the broker and acks on the producer. The former controls the minimum number of replicas that must acknowledge a write for it to be considered successful when a producer sets acks to “all.” The latter controls the number of acknowledgments the producer requires the leader to have received before considering a request complete. For example, with a topic that has a replication factor of three, min.insync.replicas needs to be set to two and acks set to “all.” This will, in effect, require a quorum of two replicas to process writes.

Another caveat with Kafka is unclean leader elections. That is, if all replicas become unavailable, there are two options: choose the first replica to come back to life (not necessarily in the ISR) and elect this replica as leader (which could result in data loss) or wait for a replica in the ISR to come back to life and elect it as leader (which could result in prolonged unavailability). Initially, Kafka favored availability by default by choosing the first strategy. If you preferred consistency, you needed to set unclean.leader.election.enable to false. However, as of 0.11, unclean.leader.election.enable now defaults to this.

Fundamentally, durability and consistency are at odds with availability. If there is no quorum, then no reads or writes can be accepted and the cluster is unavailable. This is the crux of the CAP theorem.

In part three of this series, we will discuss scaling message delivery in the distributed log.

Follow @tyler_treat