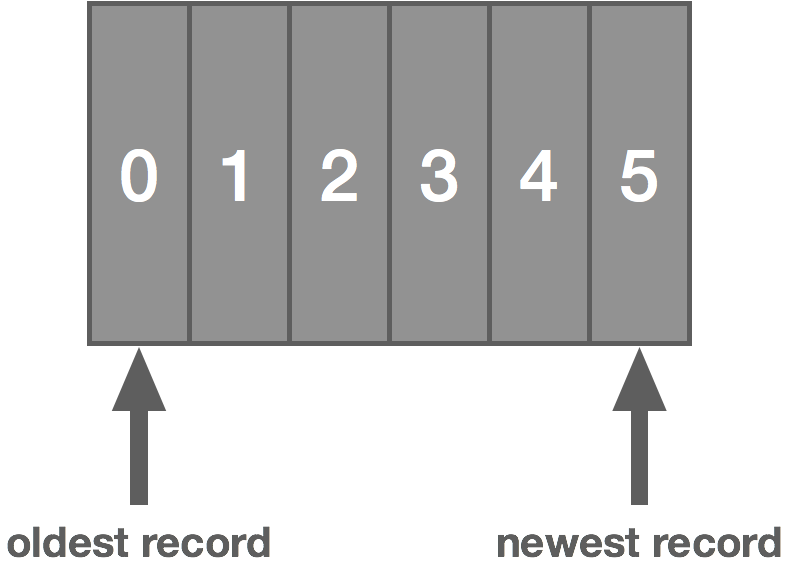

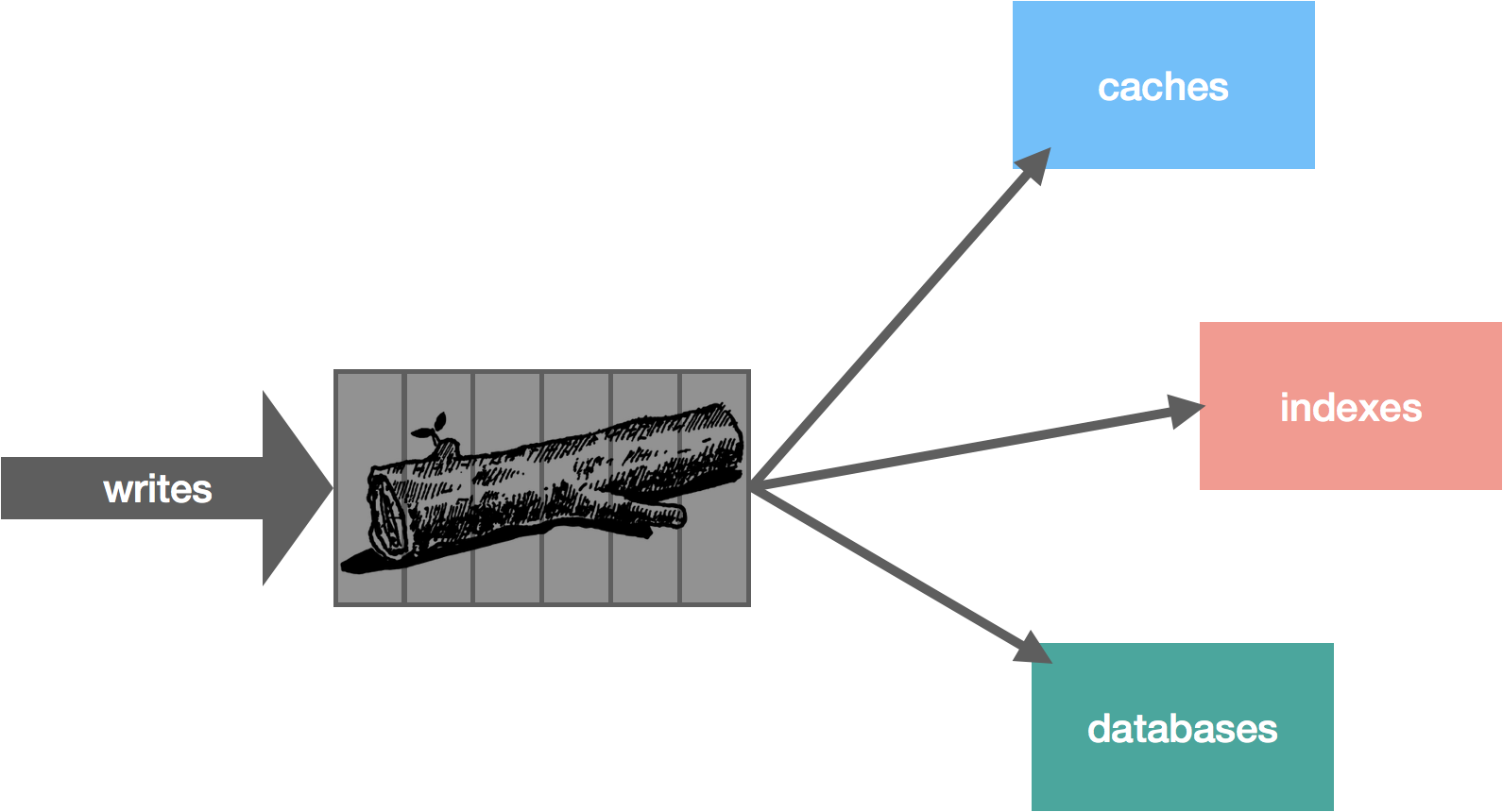

The log is a totally-ordered, append-only data structure. It’s a powerful yet simple abstraction—a sequence of immutable events. It’s something that programmers have been using for a very long time, perhaps without even realizing it because it’s so simple. Whether it’s application logs, system logs, or access logs, logging is something every developer uses on a daily basis. Essentially, it’s a timestamp and an event, a when and a what, and typically appended to the end of a file. But when we generalize that pattern, we end up with something much more useful for a broad range of problems. It becomes more interesting when we look at the log not just as a system of record but a central piece in managing data and distributing it across the enterprise efficiently.

There are a number of implementations of this idea: Apache Kafka, Amazon Kinesis, NATS Streaming, Tank, and Apache Pulsar to name a few. We can probably credit Kafka with popularizing the idea.

I think there are at least three key priorities for the effectiveness of one of these types of systems: performance, high availability, and scalability. If it’s not fast enough, the data becomes decreasingly useful. If it’s not highly available, it means we can’t reliably get our data in or out. And if it’s not scalable, it won’t be able to meet the needs of many enterprises.

When we apply the traditional pub/sub semantics to this idea of a log, it becomes a very useful abstraction that applies to a lot of different problems.

In this series, we’re not going to spend much time discussing why the log is useful. Jay Kreps has already done the legwork on that with The Log: What every software engineer should know about real-time data’s unifying abstraction. There’s even a book on it. Instead, we will focus on what it takes to build something like this using Kafka and NATS Streaming as case studies of sorts—Kafka because of its ubiquity, NATS Streaming because it’s something with which I have personal experience. We’ll look at a few core components like leader election, data replication, log persistence, and message delivery. Part one of this series starts with the storage mechanics. Along the way, we will also discuss some lessons learned while building NATS Streaming, which is a streaming data layer on top of the NATS messaging system. The intended outcome of this series is threefold: to learn a bit about the internals of a log abstraction, to learn how it can achieve the three goals described above, and to learn some applied distributed systems theory.

With that in mind, you will probably never need to build something like this yourself (nor should you), but it helps to know how it works. I also find that software engineering is all about pattern matching. Many types of problems look radically different but are surprisingly similar. Some of these ideas may apply to other things you come across. If nothing else, it’s just interesting.

Let’s start by looking at data storage since this is a critical part of the log and dictates some other aspects of it. Before we dive into that, though, let’s highlight some first principles we’ll use as a starting point for driving our design.

As we know, the log is an ordered, immutable sequence of messages. Messages are atomic, meaning they can’t be broken up. A message is either in the log or not, all or nothing. Although we only ever add messages to the log and never remove them (as with a message queue), the log has a notion of message retention based on some policies, which allows us to control how the log is truncated. This is a practical requirement since otherwise the log will grow endlessly. These policies might be based on time, number of messages, number of bytes, etc.

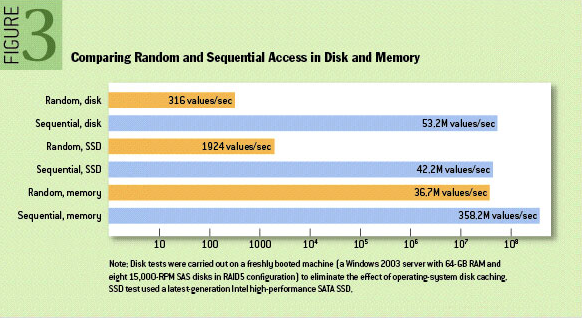

The log can be played back from any arbitrary position. With position, we normally refer to a logical message timestamp rather than a physical wall-clock time, such as an offset into the log. The log is stored on disk, and sequential disk access is actually relatively fast. The graphic below taken from the ACM Queue article The Pathologies of Big Data helps bear this out (this is helpfully pointed out by Kafka’s documentation).

That said, modern OS page caches mean that sequential access often avoids going to disk altogether. This is because the kernel keeps cached pages in otherwise unused portions of RAM. This means both reads and writes go to the in-memory page cache instead of disk. With Kafka, for example, we can verify this quite easily by running a simple test that writes some data and reads it back and looking at disk IO using iostat. After running such a test, you will likely see something resembling the following, which shows the number of blocks read and written is exactly zero.

avg-cpu: %user %nice %system %iowait %steal %idle

13.53 0.00 11.28 0.00 0.00 75.19

Device: tps Blk_read/s Blk_wrtn/s Blk_read Blk_wrtn

xvda 0.00 0.00 0.00 0 0

With the above in mind, our log starts to look an awful lot like an actual logging file, but instead of timestamps and log messages, we have offsets and opaque data messages. We simply add new messages to the end of the file with a monotonically increasing offset.

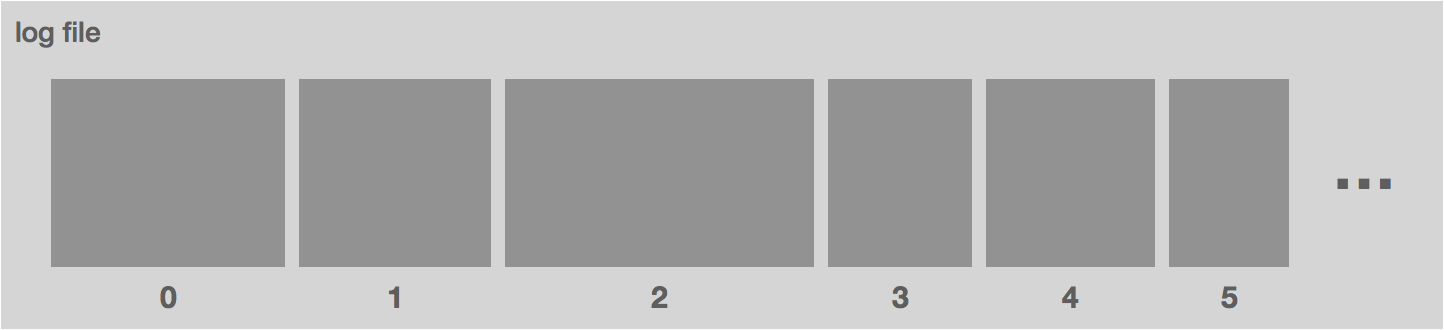

However, there are some problems with this approach. Namely, the file is going to get very, very large. Recall that we need to support a few different access patterns: looking up messages by offset and also truncating the log using a variety of different retention policies. Since the log is ordered, a lookup is simply a binary search for the offset, but this is expensive with a large log file. Similarly, aging out data by retention policy is harder.

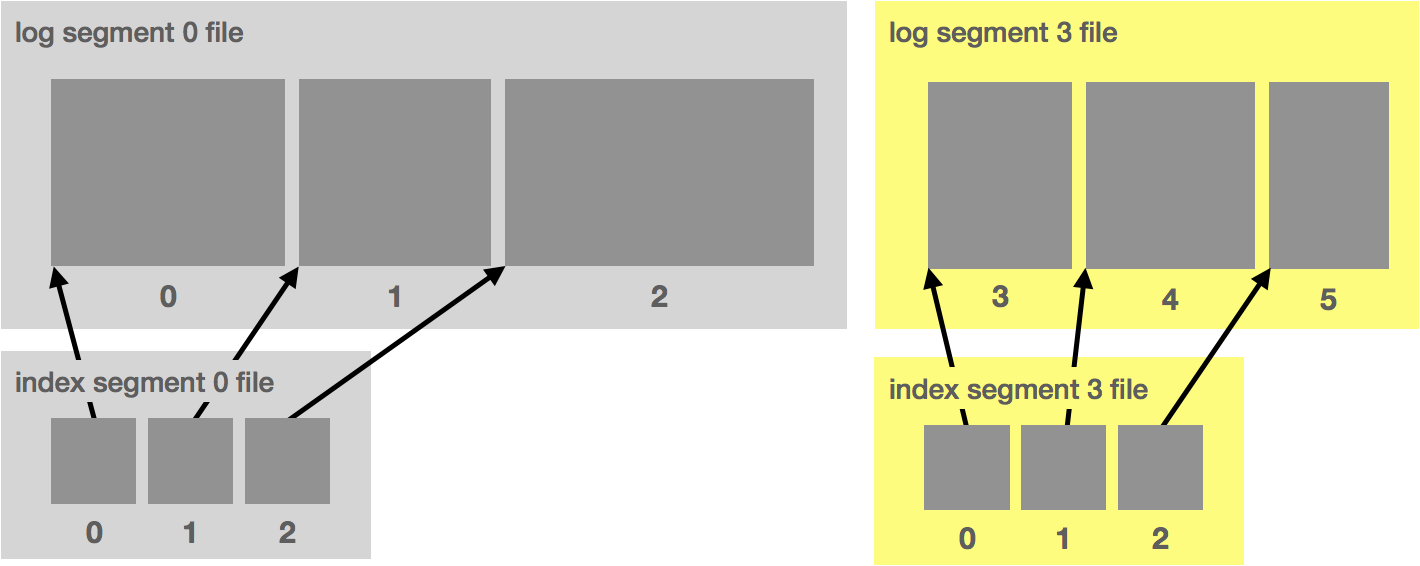

To account for this, we break up the log file into chunks. In Kafka, these are called segments. In NATS Streaming, they are called slices. Each segment is a new file. At a given time, there is a single active segment, which is the segment messages are written to. Once the segment is full (based on some configuration), a new one is created and becomes active.

Segments are defined by their base offset, i.e. the offset of the first message stored in the segment. In Kafka, the files are also named with this offset. This allows us to quickly locate the segment in which a given message is contained by doing a binary search.

Alongside each segment file is an index file that maps message offsets to their respective positions in the log segment. In Kafka, the index uses 4 bytes for storing an offset relative to the base offset and 4 bytes for storing the log position. Using a relative offset is more efficient because it means we can avoid storing the actual offset as an int64. In NATS Streaming, the timestamp is also stored to do time-based lookups.

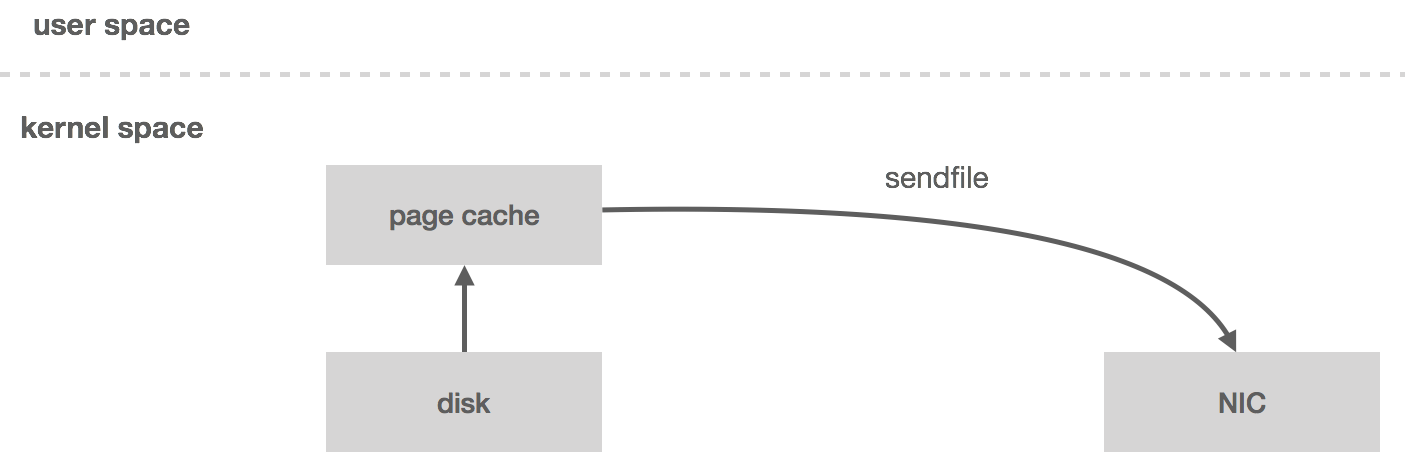

Ideally, the data written to the log segment is written in protocol format. That is, what gets written to disk is exactly what gets sent over the wire. This allows for zero-copy reads. Let’s take a look at how this otherwise works.

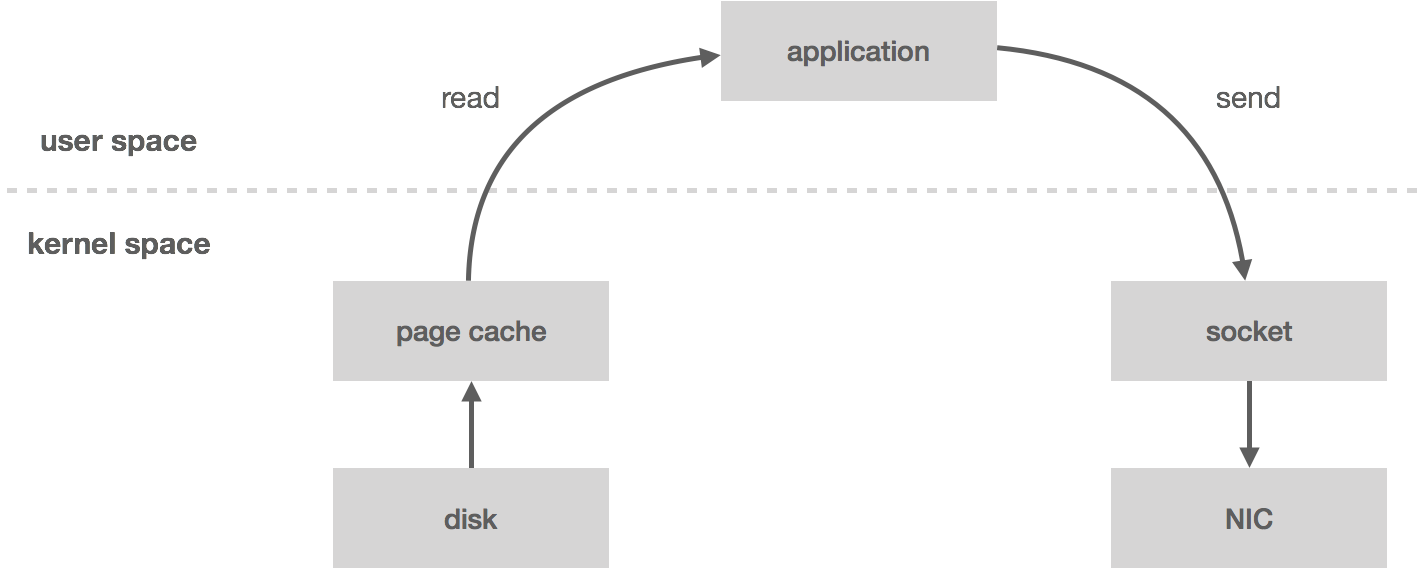

When you read messages from the log, the kernel will attempt to pull the data from the page cache. If it’s not there, it will be read from disk. The data is copied from disk to page cache, which all happens in kernel space. Next, the data is copied into the application (i.e. user space). This all happens with the read system call. Now the application writes the data out to a socket using send, which is going to copy it back into kernel space to a socket buffer before it’s copied one last time to the NIC. All in all, we have four copies (including one from page cache) and two system calls.

However, if the data is already in wire format, we can bypass user space entirely using the sendfile system call, which will copy the data directly from the page cache to the NIC buffer—two copies (including one from page cache) and one system call. This turns out to be an important optimization, especially in garbage-collected languages since we’re bringing less data into application memory. Zero-copy also reduces CPU cycles and memory bandwidth.

NATS Streaming does not currently make use of zero-copy for a number of reasons, some of which we will get into later in the series. In fact, the NATS Streaming storage layer is actually pluggable in that it can be backed by any number of mediums which implement the storage interface. Out of the box it includes the file-backed storage described above, in-memory, and SQL-backed.

There are a few other optimizations to make here such as message batching and compression, but we’ll leave those as an exercise for the reader.

In part two of this series, we will discuss how to make this log fault tolerant by diving into data-replication techniques.

Follow @tyler_treat