I think it’s safe to say Kubernetes has “won” the cloud mindshare game. If you look at the CNCF Cloud Native landscape (and manage to not go cross eyed), it seems like most of the projects are somehow related to Kubernetes. KubeCon is one of the fastest-growing industry events. Companies we talk to at Real Kinetic who are either preparing for or currently executing migrations to the cloud are centering their strategies around Kubernetes. Those already in the cloud are investing heavily in platform-izing their Kubernetes environment. Kubernetes competitors like Nomad, Pivotal Cloud Foundry, OpenShift, and Rancher have sort of just faded to the background (or simply pivoted to Kubernetes). In many ways, “cloud native” seems to be equated with “Kubernetes”.

All this is to say, the industry has coalesced around Kubernetes as the way to do cloud. But after working with enough companies doing cloud, watching their experiences, and understanding their business problems, I can’t help but wonder: should it be? Or rather, is Kubernetes actually the right level of abstraction?

Going k8sless

While we’ve worked with a lot of companies doing Kubernetes, we’ve also worked with some that are deliberately not. Instead, they leaned into serverless—heavily—or as I like to call it, they’ve gone k8sless. These are not small companies or startups, they are name brands you would recognize.

At first, we were skeptical. Our team came from a company that made it all the way to IPO using Google App Engine, one of the earliest serverless platforms available. We have regularly espoused the benefits of serverless. We’ve talked to clients about how they should consider it for their own workloads (often to great skepticism). But using only serverless? For once, we were the serverless skeptics. One client in particular was beginning a migration of their e-commerce platform to Google Cloud. They wanted to do it completely serverless. We gave our feedback and recommendations based on similar migrations we’ve performed:

“There are workloads that aren’t a good fit.”

“It would require major re-architecting.”

“It will be expensive once fully migrated.”

“You’ll have better cost efficiency bin packing lots of services into VMs with Kubernetes.”

We articulated all the usual arguments made by the serverless doubters. Even Google was skeptical, echoing our sentiments to the customer. “Serious companies doing online retail like The Home Depot or Target are using Google Kubernetes Engine,” was more or less the message. We have a team of serverless experts at Real Kinetic though, so we forged ahead and helped execute the migration.

Fast forward nearly three years later and we will happily admit it: we were wrong. You can run a multibillion-dollar e-commerce platform without a single VM. You don’t have to do a full rewrite or major re-architecting. It can be cost-effective. It doesn’t require proprietary APIs or constraints that result in vendor lock-in. It might sound like an exaggeration, but it’s not.

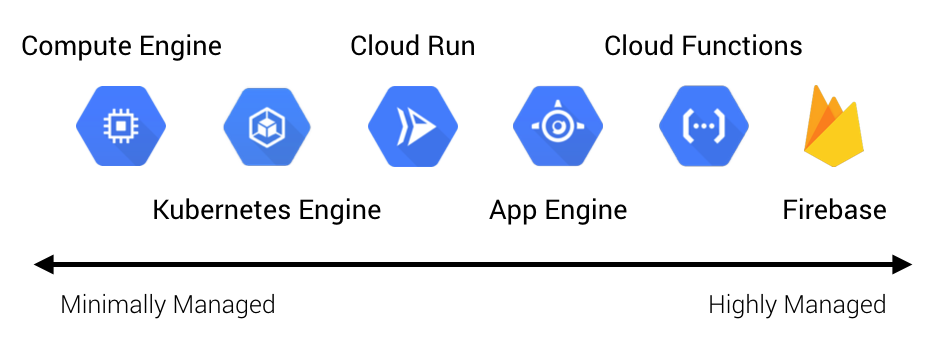

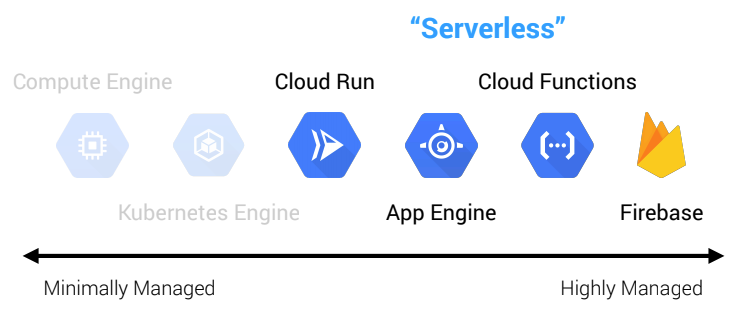

Container as the interface

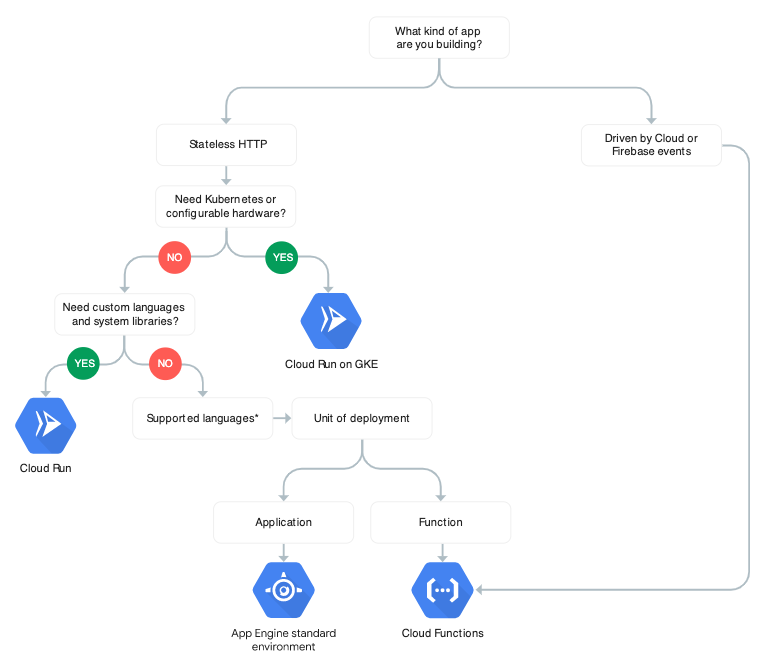

Over the last several years, Google’s serverless offerings have evolved far beyond App Engine. It has reached the point where it’s now viable to run a wide variety of workloads without much issue. In particular, Cloud Run offers many of the same benefits of a PaaS like App Engine without the constraints. If your code can run in a container, there’s a very good chance it will run on Cloud Run with little to no modification.

In fact, other than using the gcloud CLI to deploy a service, there’s nothing really Google- or Cloud Run-specific needed to get a functioning application. This is because Cloud Run uses Knative, an open-source Kubernetes-based platform, as its deployment interface. And while Cloud Run is a Google-managed backend for the Knative interface, we could just as well switch the backend to GKE or our own Kubernetes cluster. When we implement our Cloud Run services, we actually implement them using a Kubernetes Deployment manifest, shown below, and right before deploying, we swap Deployment for Knative’s Service manifest.

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

cloud.googleapis.com/location: us-central1

service: my-service

name: my-service

spec:

template:

spec:

containers:

- image: us.gcr.io/my-project/my-service:v1

name: my-service

ports:

- containerPort: 8080

resources:

limits:

cpu: 2

memory: 1024MiThis means we can deploy to Kubernetes without Knative at all, which we often do during development using the combination of Skaffold and K3s to perform local testing. It also allows us to use Kubernetes native tooling such as Kustomize to manage configuration. Think of Cloud Run as a Kubernetes Deployment as a service (though really more like Deployment and Service…as a service).

“Normal” businesses versus internet-scale businesses

What about cost? Yes, the unit cost in terms of compute is higher with serverless. If you execute enough CPU cycles to fill the capacity of a VM, you are better off renting the whole VM as opposed to effectively renting timeshares of it. But here’s the thing: most “normal” businesses tend to have highly cyclical traffic patterns throughout the day and their scale is generally modest.

What do I mean by “normal” businesses? These are primarily non-internet-scale companies such as insurance, fast food, car rental, construction, or financial services, not Google, Netflix, or Amazon. As a result, these companies can benefit greatly from pay-per-use, and those in the retail space also benefit greatly from the elasticity of this model during periods like Black Friday or promotional campaigns. Businesses with brick-and-mortar have traffic that generally follows their operating hours. During off-hours, they can often scale quite literally to zero.

Many of these businesses, for better or worse, treat software development as an IT cost center to be managed. They don’t need—or for that matter, want—the costs and overheads associated with platform-izing Kubernetes. A lot of the companies we interact with fall into this category of “normal” businesses, and I suspect most companies outside of tech do as well.

BYOP—Bring Your Own Platform

I’ve asked it before: is Kubernetes really the end-game abstraction? In my opinion, it’s an implementation detail. I don’t think I’m alone in that opinion. Some companies put a tremendous amount of investment into abstracting Kubernetes from their developers. This is what I mean by “platform-izing” Kubernetes. It typically involves significant and ongoing OpEx investment. The industry has started to coalesce around two concepts that encapsulate this: Platform Engineering and Internal Developer Platform. So while Kubernetes may have become the default container orchestrator, the higher-level pieces—the pieces constituting the Internal Developer Platform—are still very much bespoke. Kelsey Hightower said it best: the majority of people managing infrastructure just want a PaaS. The only requirement: it has to be built by them. That’s a problem.

Imagine having a Kubernetes cluster per Deployment. Full blast radius isolation, complete cost traceability, granular yet simple permissioning. It sounds like a maintenance nightmare though, right? Now imagine those clusters just being hidden from you completely and the Deployment itself is the only thing you interact with and maintain. You just provide your container (or group of containers), configure your CPU and memory requirements, specify the network and resource access, and deploy it. The Deployment manages your load balancing and ingress, automatically scales the pods up and down or canaries traffic, and gives you aggregated logs and metrics out of the box. You only pay for the resources consumed while processing a request. Just a few years ago, this was a futuristic-sounding fantasy.

The platform Kelsey describes above does now exist. From my experience, it’s a nearly ideal solution for those “normal” businesses who are looking to minimize complexity and operational costs and avoid having to bring (more like build) their own platform. I realize GCP is a distant third when it comes to public cloud market share so this will largely fall on deaf ears, but for those who are still listening: stop wasting time on Kubernetes and just use Cloud Run. Let me expand on the reasons why.

- Easily and quickly get started with the cloud. Many of the companies we work with who are still in the midst of migrating to the cloud get hung up with analysis paralysis. Cloud Run isn’t a perfect solution for everything, but it’s good enough for the majority of cases. The rest can be handled as exceptions.

- Minimize complexity of cloud environments. Cloud Run does not eliminate the need for infrastructure (there are still caches, queues, databases, and so forth), but it greatly simplifies it. Using managed services for the remaining infrastructure pieces simplifies it further.

- Increase the efficiency of your developers and reduce operational costs. Rather than spending most of their time dealing with infrastructure concerns, allow your developers to focus on delivering business value. For most businesses, infrastructure is undifferentiated commodity work. By “outsourcing” large parts of your undifferentiated Internal Developer Platform, you can reallocate developers to product or feature development and reduce operational costs. This allows you to get the benefits of Platform Engineering with a fraction of the maintenance and overhead. Lastly, if you are a “normal” business that doesn’t operate at internet scale and has fairly cyclical traffic, it’s entirely likely Cloud Run will be cheaper than VM-based platforms.

- Maintain the flexibility to evolve to a more complex solution over time if needed. This is where traditional serverless platforms and PaaS solutions fall short. Again, with Cloud Run there is no actual vendor lock-in, it’s just a Kubernetes Deployment as a Service. Even without Knative, we can take that Deployment and run it in any Kubernetes cluster. This is a very different paradigm from, say, App Engine where you wrote your application using App Engine APIs and deployed your service to the App Engine runtime. In this new paradigm, the artifact is a Plain Old Container. There are cases where Cloud Run is not a good fit, such as certain kinds of stateful legacy applications or services with sustained, non-cyclical traffic. We don’t want to be painted into a corner with these types of situations so having flexibility is important.

There are similar analogs to Cloud Run on other cloud platforms. For example, AWS has AppRunner. However, in my experience these fall short in terms of developer experience because of either lack of investment from the cloud provider or environment complexity (as I would argue is the case for AWS). Managed services like Cloud Run are one of the areas that GCP truly excels and differentiates itself.

Just use Cloud Run, seriously

I realize not everyone will be convinced. The gravitational pull of Kubernetes is strong and as a platform, it’s a safe bet. However, operationalizing Kubernetes properly—whether it’s a managed offering like GKE or not—requires some kind of platform team and ongoing investment. We’ve seen it approached without this where developers are given clusters or allowed to spin them up and fend for themselves. This quickly becomes untenable because standards are non-existent, security and compliance is unmanageable, and developer time is split between managing infrastructure and actual feature development.

If your organization is unable or unwilling to make this investment, I urge you to consider Cloud Run. There’s still work needed on the periphery to properly operationalize it, such as implementing CI/CD pipelines and managing accessory infrastructure, but it’s a much lower investment. Additionally, it provides an escape hatch—unlike App Engine or traditional PaaS solutions, there is no real switching cost in moving to Kubernetes if you need to in the future. With Cloud Run, serverless has finally reached a tipping point where it’s now viable for a majority of workloads rather than a niche subset. Unlike Kubernetes, it provides the right level of abstraction for most businesses building software. In my opinion, serverless is still not taken seriously due to preconceived notions, but it’s time to start reevaluating those notions.

Agree? Disagree? I’d love to hear your thoughts. If you’re an organization that would like to do cloud differently or are looking for the playbook to operationalize Google Cloud Platform, please get in touch.

Follow @tyler_treat