Real Kinetic often works with companies just beginning their cloud journey. Many come from a conventional on-prem IT organization, which typically looks like separate development and IT operations groups. One of the main challenges we help these clients with is how to structure their engineering organizations effectively as they make this transition. While we approach this problem holistically, it can generally be looked at as two components: product development and infrastructure. One might wonder if this is still the case with the shift to DevOps and cloud, but as we’ll see, these two groups still play important and distinct roles.

We help clients understand and embrace the notion of a product mindset as it relates to software development. This is a fundamental shift from how many of these companies have traditionally developed software, in which development was viewed as an IT partner beholden to the business. This transformation is something I’ve discussed at length and will not be the subject of this conversation. Rather, I want to spend some time talking about the other side of the coin: operations.

Operations in the Cloud

While I’ve talked about operations in the context of cloud before, it’s only been in broad strokes and not from a concrete, organizational perspective. Those discussions don’t really get to the heart of the matter and the question that so many IT leaders ask: what does an operations organization look like in the cloud?

This, of course, is a highly subjective question to which there is no “right” answer. This is doubly so considering that every company and culture is different. I can only humbly offer my opinion and answer with what I’ve seen work in the context of particular companies with particular cultures. Bear this in mind as you think about your own company. More often than not, the cultural transformation is more arduous than the technology transformation.

I should also caveat that—outside of being a strategic instrument—Real Kinetic is not in the business of simply helping companies lift-and-shift to the cloud. When we do, it’s always with the intention of modernizing and adapting to more cloud-native architectures. Consequently, our clients are not usually looking to merely replicate their current org structure in the cloud. Instead, they’re looking to tailor it appropriately.

Defining Lines of Responsibility

What should developers need to understand and be responsible for? There tend to be two schools of thought at two different extremes when it comes to this depending on peoples’ backgrounds and experiences. Oftentimes, developers will want more control over infrastructure and operations, having come from the constraints of a more siloed organization. On the flip side, operations folks and managers will likely be more in favor of having a separate group retain control over production environments and infrastructure for various reasons—efficiency, stability, and security to name a few. Not to mention, there are a lot of operational concerns that many developers are likely not even aware of—the sort of unsung, unglamorous bits of running software.

Ironically, both models can be used as an argument for “DevOps.” There are also cases to be made for either. The developer argument is better delivery velocity and innovation at a team level. The operations argument is better stability, risk management, and cost control. There’s also likely more potential for better consistency and throughput at an organization level.

The answer, unsurprisingly, is a combination of both.

There is an inherent tension between empowering developers and running an efficient organization. We want to give developers the flexibility and autonomy they need to develop good solutions and innovate. At the same time, we also need to realize the operational efficiencies that common solutions and standardization provide in order to benefit from economies of scale. Should every developer be a generalist or should there be specialists?

Real Kinetic helps clients adopt a model we refer to as “Developer Enablement.” The idea of Developer Enablement is shifting the focus of ops teams from being “masters” of production to “enablers” of production by applying a product lens to operations. In practical terms, this means less running production workloads on behalf of developers and more providing tools and products that allow developers to run workloads themselves. It also means thinking of operations less as a task-driven service model and more as a strategic enabler. However, Developer Enablement is not about giving full autonomy to developers to do as they please, it’s about providing the abstractions they need to be successful on the platform while realizing the operational efficiencies possible in a larger organization. This means providing common tooling, products, and patterns. These are developed in partnership with product teams so that they meet the needs of the organization. Some companies might refer to this as a “platform” team, though I think this has a slightly different meaning. So how does this map to an actual organization?

Mapping Out an Engineering Organization

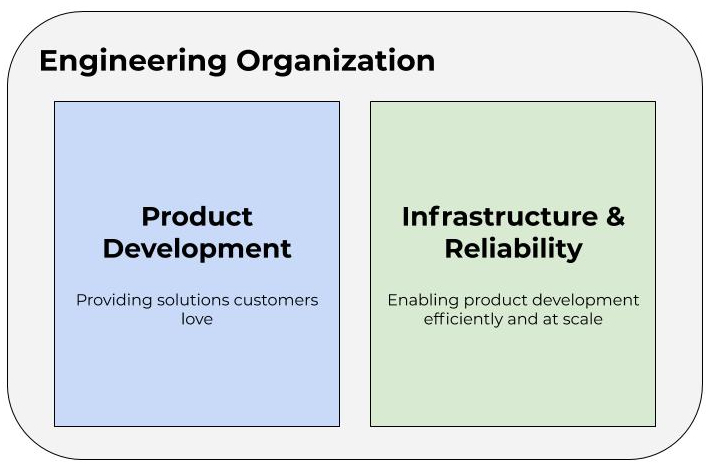

First, let’s mentally model our engineering organization as two groups: Product Development and Infrastructure and Reliability. The first is charged with developing products for end users and customers. This is the stuff that makes the business money. The second is responsible for supporting the first. This is where the notion of “developer enablement” comes into play. And while this group isn’t necessarily doing work that is directly strategic to the business, it is work that is critical to providing efficiencies and keeping the lights on just the same. This would traditionally be referred to as Operations.

As mentioned above, the focus of this discussion is the green box. And as you might infer from the name, this group is itself composed of two subgroups. Infrastructure is about enabling product teams, and Reliability is about providing a first line of defense when it comes to triaging production incidents. This latter subgroup is, in and of itself, its own post and worthy of a separate discussion, so we’ll set that aside for another day. We are really focused on what a cloud infrastructure organization might look like. Let’s drill down on that piece of the green box.

An Infrastructure Organization Model

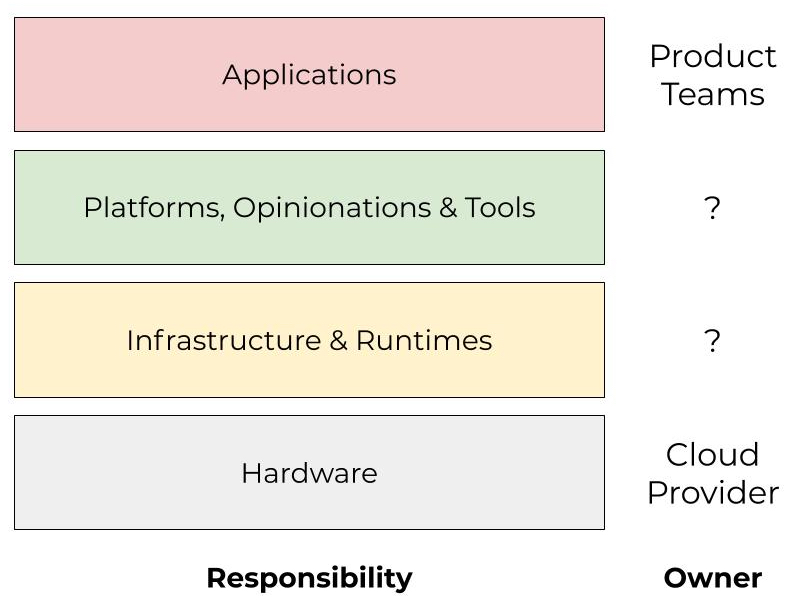

When thinking about organization structure, I find that it helps to consider layers of operational concern while mapping the ownership of those concerns. The below diagram is an example of this. Note that these do not necessarily map to specific team boundaries. Some areas may have overlap, and responsibilities may also shift over time. This is mostly an exercise to identify key organizational needs and concerns.

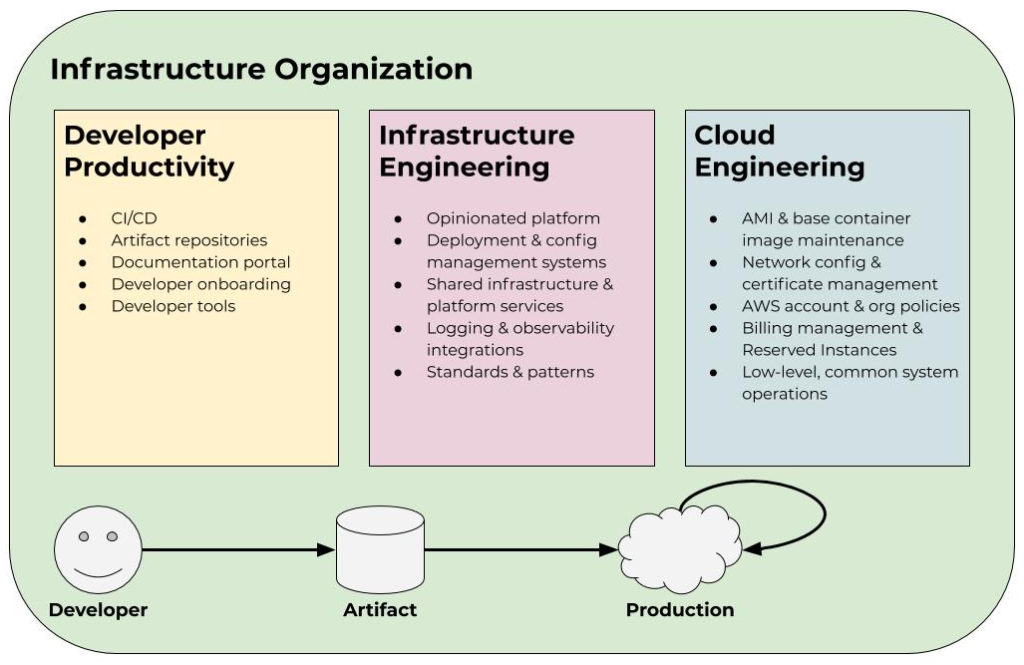

We like to model the infrastructure organization as three teams: Developer Productivity, Infrastructure Engineering, and Cloud Engineering. Each team has its own charter and mission, but they are all in support of the overarching objective of enabling product development efficiently and at scale. In some cases, these teams consist of just a handful of engineers, and in other cases, they consist of dozens or hundreds of engineers depending on the size of the organization and its needs. These team sizes also change as the priorities and needs of the company evolve over time.

Developer Productivity

Developer Productivity is tasked with getting ideas from an engineer’s brain to a deployable artifact as efficiently as possible. This involves building or providing solutions for things like CI/CD, artifact repositories, documentation portals, developer onboarding, and general developer tooling. This team is primarily an engineering spend multiplier. Often a small Developer Productivity team can create a great deal of leverage by providing these different tools and products to the organization. Their core mandate is reducing friction in the delivery process.

Infrastructure Engineering

The Infrastructure Engineering team is responsible for making the process of getting a deployable artifact to production and managing it as painless as possible for product teams. Often this looks like providing an “opinionated platform” on top of the cloud provider. Completely opening up a platform such as AWS for developers to freely use can be problematic for larger organizations because of cost and time inefficiencies. It also makes security and compliance teams’ jobs much more difficult. Therefore, this group must walk the fine line between providing developers with enough flexibility to be productive and move fast while ensuring aggregate efficiencies to maintain organization-wide throughput as well as manage costs and risk. This can look like providing a Kubernetes cluster as a service with opinions around components like load balancing, logging, monitoring, deployments, and intra-service communication patterns. Infrastructure Engineering should also provide tooling for teams to manage production services in a way that meets the organization’s regulatory requirements.

The question of ownership is important. In some organizations, the Infrastructure Engineering team may own and operate infrastructure services, such as common compute clusters, databases, or message queues. In others, they might simply provide opinionated guard rails around these things. Most commonly, it is a combination of both. Without this, it’s easy to end up with every team running their own unique messaging system, database, cache, or other piece of infrastructure. You’ll have lots of architecture astronauts on your hands, and they will need to be able to answer questions around things like high availability and disaster recovery. This leads to significant inefficiencies and operational issues. Even if there isn’t shared infrastructure, it’s valuable to have an opinionated set of technologies to consolidate institutional knowledge, tooling, patterns, and practices. This doesn’t have to act as a hard-and-fast rule, but it means teams should be able to make a good case for operating outside of the guard rails provided.

This model is different from traditional operations in that it takes a product-mindset approach to providing solutions to internal customers. This means it’s important that the group is able to understand and empathize with the product teams they serve in order to identify areas for improvement. It also means productizing and automating traditional operations tasks while encouraging good patterns and practices. This is a radical departure from the way in which most operations teams normally operate. It’s closer to how a product development team should work.

This group should also own standards around things like logging and instrumentation. These standards allow the team to develop tools and services that deal with this data across the entire organization. I’ve talked about this notion with the Observability Pipeline.

Cloud Engineering

Cloud Engineering might be closest to what most would consider a conventional operations team. In fact, we used to refer to this group as Cloud Operations but have since moved away from that vernacular due to the connotation the word “operations” carries. This group is responsible for handling common low-level concerns, underlying subsystems management, and realizing efficiencies at an aggregate level. Let’s break down what that means in practice by looking at some examples. We’ll continue using AWS to demonstrate, but the same applies across any cloud provider.

One of the low-level concerns this group is responsible for is AMI and base container image maintenance. This might be the AMIs used for Kubernetes nodes and the base images used by application pods running in the cluster. These are critical components as they directly relate to the organization’s security and compliance posture. They are also pieces most developers in a large organization are not well-equipped to—or interested in—dealing with. Patch management is a fundamental concern that often takes a back seat to feature development. Other examples of this include network configuration, certificate management, logging agents, intrusion detection, and SIEM. These are all important aspects of keeping the lights on and the company’s name out of the news headlines. Having a group that specializes in these shared operational concerns is vital.

In terms of realizing efficiencies, this mostly consists of managing AWS accounts, organization policies (another important security facet), and billing. This group owns cloud spend across the organization and, as a result, is able to monitor cumulative usage and identify areas for optimization. This might look like implementing resource-tagging policies, managing Reserved Instances, or negotiating with AWS on committed spend agreements. Spend is one of the reasons large companies standardize on a single cloud platform, so it’s essential to have good visibility and ownership over this. Note that this team is not responsible for the spend itself, rather they are responsible for visibility into the spend and cost allocations to hold teams accountable.

The unfortunate reality is that if the Cloud Engineering team does their job well, no one really thinks about them. That’s just the nature of this kind of work, but it has a massive impact on the company’s bottom line.

Summary

Depending on the company culture, words like “standards” and “opinionated” might be considered taboo. These can be especially unsettling for developers who have worked in rigid or siloed environments. However, it doesn’t have to be all or nothing. These opinions are more meant to serve as a beaten path which makes it easier and faster for teams to deliver products and focus on business value. In fact, opinionation will accelerate cloud adoption for many organizations, enable creativity on the value rather than solution architecture, and improve efficiency and consistency at a number of levels like skills, knowledge, operations, and security. The key is in understanding how to balance this with flexibility so as to not overly constrain developers.

We like taking a product approach to operations because it moves away from the “ticket-driven” and gatekeeper model that plagues so many organizations. By thinking like a product team, infrastructure and operations groups are better able to serve developers. They are also better able to scale—something that is consistently difficult for more interrupt-driven ops teams who so often find themselves becoming the bottleneck.

Notice that I’ve entirely sidestepped terms like “DevOps” and “SRE” in this discussion. That is intentional as these concepts frequently serve as a distraction for companies who are just beginning their journey to the cloud. There are ideas encapsulated by these philosophies which provide important direction and practices, but it’s imperative to not get too caught up in the dogma. Otherwise, it’s easy to spin your wheels and chase things that, at least early on, are not particularly meaningful. It’s more impactful to focus on fundamentals and finding some success early on versus trying to approach things as town planners.

Moreover, for many companies, the organization model I walked through above was the result of evolving and adapting as needs changed and less of a wholesale reorg. In the spirit of product mindset, we encourage starting small and iterating as opposed to boiling the ocean. The model above can hopefully act as a framework to help you identify needs and areas of ownership within your own organization. Keep in mind that these areas of responsibility might shift over time as capabilities are implemented and added.

Lastly, do not mistake this framework as something that might preclude exploration, learning, and innovation on the part of development teams. Again, opinionation and standards are not binding but rather act as a path of least resistance to facilitate efficiency. It’s important teams have a safe playground for exploratory work. Ideally, new ideas and discoveries that are shown to add value can be standardized over time and become part of that beaten path. This way we can make them more repeatable and scale their benefits rather than keeping them as one-off solutions.

How has your organization approached cloud development? What’s worked? What hasn’t? I’d love to hear from you.

Follow @tyler_treat