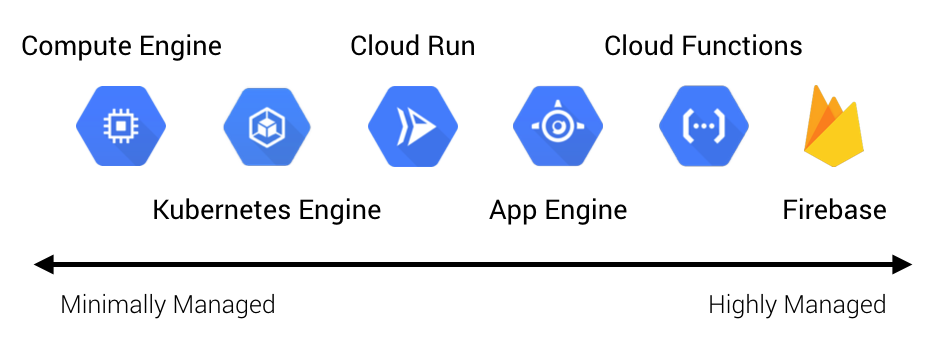

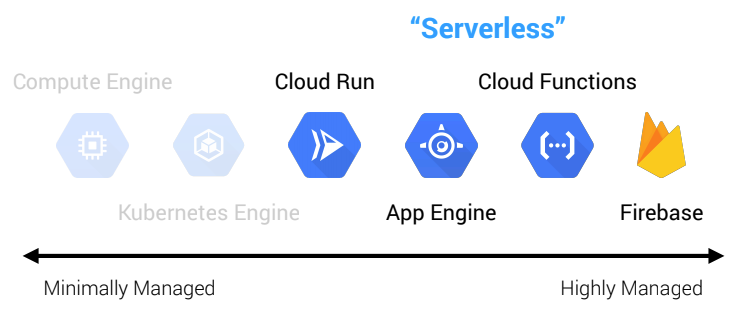

A lot of our clients at Real Kinetic leverage serverless on GCP to quickly build applications with minimal operations overhead. Serverless is one of the things that truly differentiates GCP from other cloud providers, and App Engine is a big component of this. Many of these companies come from an on-prem world and, as a result, tend to favor perimeter-based security models. They rely heavily on things like IP and network restrictions, VPNs, corporate intranets, and so forth. Unfortunately, this type of security model doesn’t always fit nicely with serverless due to the elastic and dynamic nature of serverless systems.

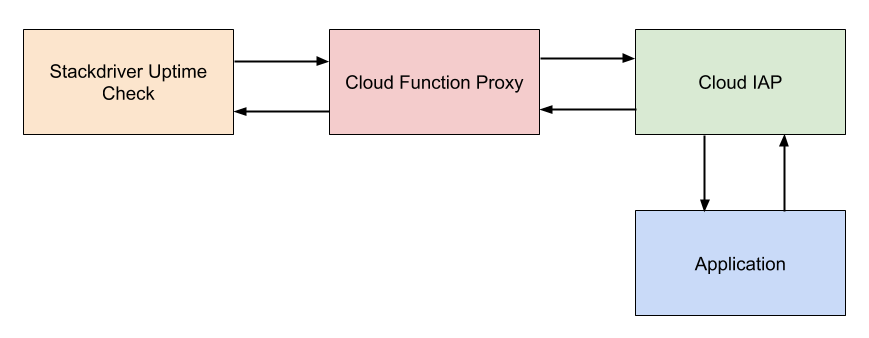

Recently, I worked with a client who was building an application for internal support staff on App Engine. They were using Identity-Aware Proxy (IAP) to authenticate users and authorize access to the application. IAP provides a fully managed solution for implementing a zero-trust access model for App Engine and Compute Engine. In this case, their G Suite user directory was backed by Active Directory, which allowed them to manage access to the application using Single Sign-On and AD groups.

Everything was great until the team hit a bit of a snag when they went through their application vulnerability assessment. Because it was for internal users, the security team requested the application be restricted to the corporate network. While I’m deeply skeptical of the value this adds in terms of security—the application was already protected by SSO and two-factor authentication and IAP cannot be bypassed with App Engine—I shared my concerns and started evaluating options. Sometimes that’s just the way things go in a larger, older organization. Culture shifts are hard and take time.

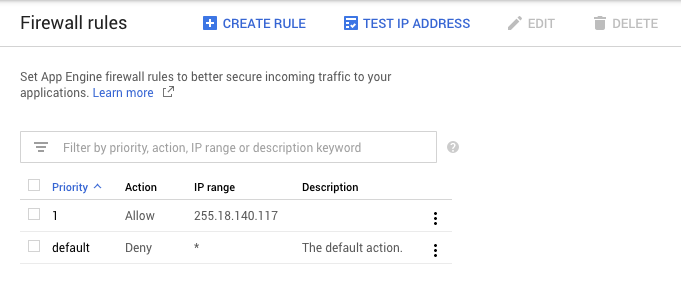

App Engine has firewall rules built in which allow you to secure incoming traffic to your application with allow/deny rules based on IP, so it seemed like an easy fix. The team would be in production in no time!

Unfortunately, there are some issues with how these firewall rules work depending on the application architecture. All traffic to App Engine goes through Google Front End (GFE) servers. This provides numerous benefits including TLS termination, DDoS protection, DNS, load balancing, firewall, and integration with IAP. It can present problems, however, if you have multiple App Engine services that communicate with each other internally. For example, imagine you have a frontend service which talks to a backend service.

App Engine does not provide a static IP address and instead relies on a large, dynamic pool of IP addresses. Two sequential outbound calls from the same application can appear to originate from two different IP addresses. One option is to allow all possible App Engine IPs, but this is riddled with issues. For one, Google uses netblocks that dynamically change and are encoded in Sender Policy Framework (SPF) records. To determine all of the IPs App Engine is currently using, you need to recursively perform DNS lookups by fetching the current set of netblocks and then doing a DNS lookup for each netblock. These results are not static, meaning you would need to do the lookups and update firewall rules continually. Worse yet, allowing all possible App Engine IPs would be self-defeating since it would be trivial for an attacker to work around by setting up their own App Engine application to gain access, assuming there isn’t any additional security beyond the firewall.

Another, slightly better option is to set up a proxy on Compute Engine in the same region as your App Engine application. With this, you get a static IP address. The downside here is that it’s an additional piece of infrastructure that must be managed, which isn’t great when you’re shooting for a serverless architecture.

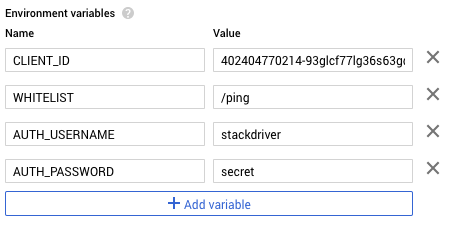

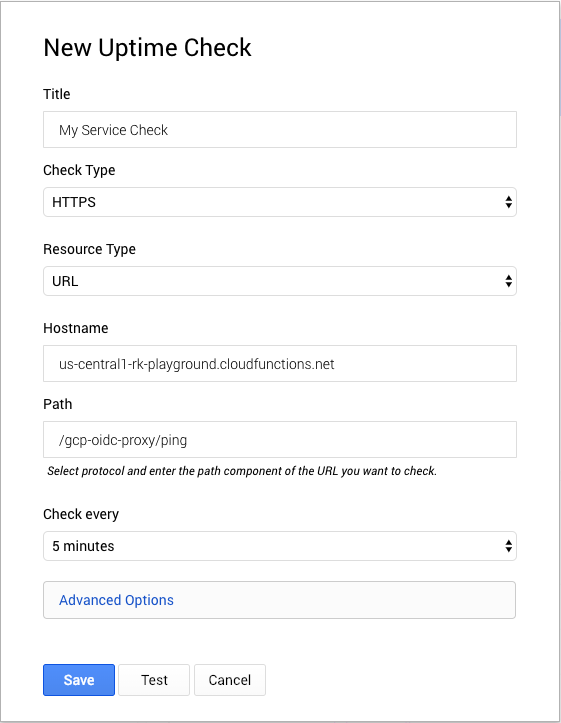

Luckily, there is a better solution—one that fits our serverless model and enables us to control external traffic while allowing App Engine services to securely communicate internally. IAP supports context-aware access, which allows enforcing granular access controls for web applications, VMs, and GCP APIs based on an end-user’s identity and request context. Essentially, context-aware access brings a richer zero-trust model to App Engine and other GCP services.

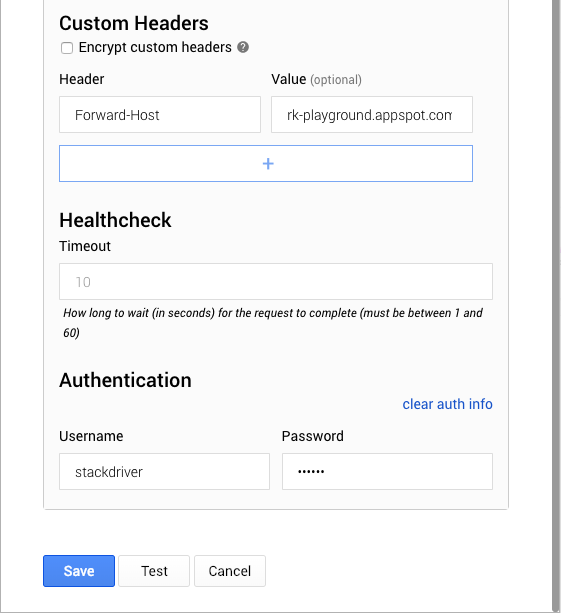

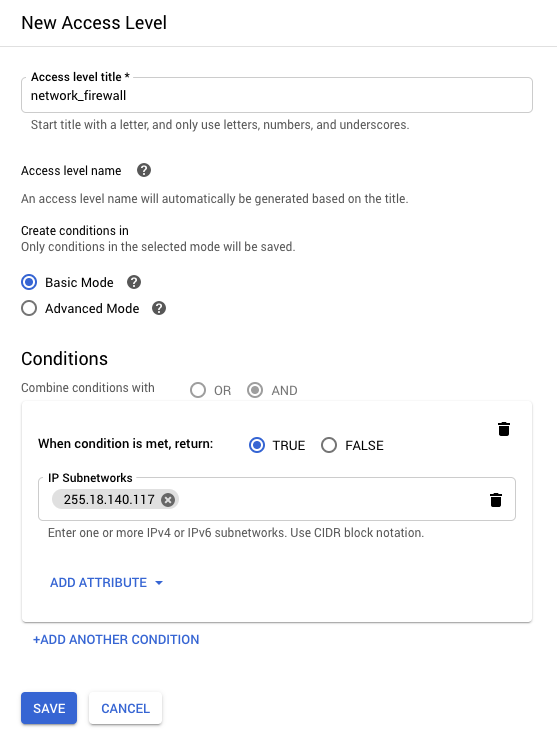

To set up a network firewall in IAP, we first need to create an Access Level in the Access Context Manager. Access Levels are a way to add an extra level of security based on request attributes such as IP address, region, time of day, or device. In the client’s case, they can create an Access Level to only allow access from their corporate network.

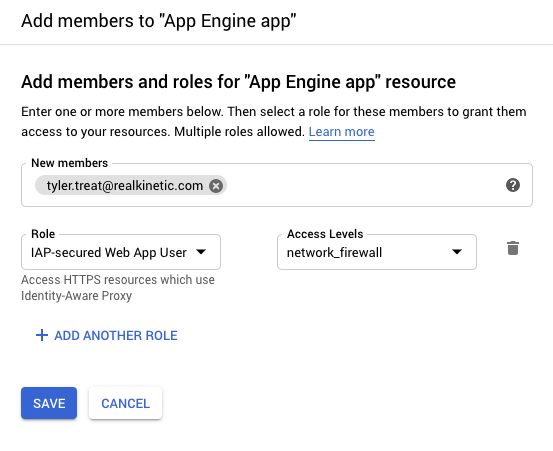

We can then add the Access Level to roles that are assigned to users or groups in IAP. This means even if users are authenticated, they must be on the corporate network to access the application.

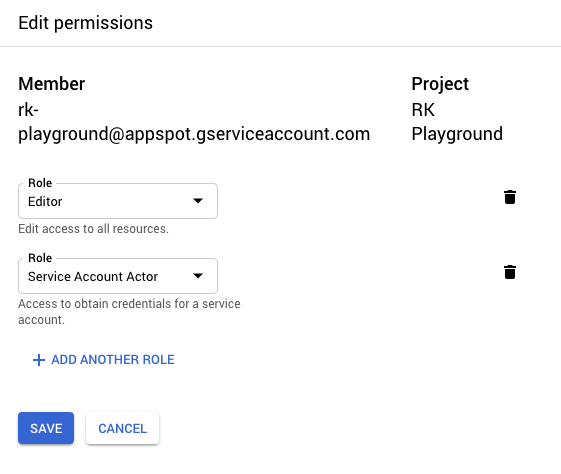

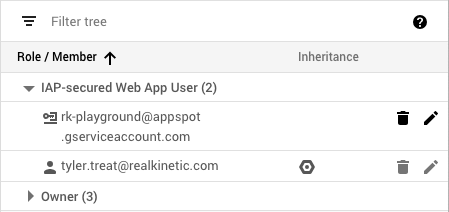

To allow App Engine services to communicate freely, we simply need to assign the IAP-secured Web App User role without the Access Level to the App Engine default service account. Services will then authenticate as usual using OpenID Connect without the added network restriction. The default service account is managed by GCP and there are no associated credentials, so this provides a solid security posture.

Now, at this point, we’ve solved the IP firewall problem, but that’s not really in the spirit of zero-trust, right? Zero-trust is a security principle believing that organizations should not inherently trust anything inside or outside of their perimeters and instead should verify anything trying to connect to their systems. Having to connect to a VPN in order to access an application in the cloud is kind of a bummer, especially when the corporate VPN goes down. COVID-19 has made a lot of organizations feel this pain. Fortunately, Access Levels can be a lot smarter than providing simple lists of approved IP addresses. With the Cloud IAM Conditions Framework, we can even write custom rules to allow access based on URL path, resource type, or other request attributes.

At this point, I talked the client through the Endpoint Verification process and how we can shift away from a perimeter-based security model to a defense-in-depth, zero-trust model. Rather than requiring the end-user to be signed in from the corporate network, we can require them to be signed in from a trusted, corporate-owned device from anywhere. We can require that the device has a screen lock and is encrypted or has a minimum OS version.

With IAP and context-aware access, we can build layered security on top of applications and resources without the need for a VPN, while still centrally managing access. This can even extend beyond GCP to applications hosted on-prem or in other cloud platforms like AWS and Azure. Enterprises don’t have to move away from more traditional security models all at once. This pattern allows you to gradually shift by adding and removing Access Levels and attributes over time. Zero-trust becomes much easier to implement within large organizations when they don’t have to flip a switch.

Follow @tyler_treat